The Ethics of Photographing the Homeless

Although I’ve had an iPhone for years, I still feel like a novice when it comes to iPhone photography. I’m still developing my own photographic style, but I feel that I’ve found the genre that suits me best: street photography. Opinions vary as to a precise definition of street photography, but for me, it’s candid photos of ordinary people, taken in a public space, that convey some degree of humanity in moments that are often fleeting.

I’m drawn to all types of people, and New York City where I currently live provides quite a variety. How I choose my subject matter tends to be visceral. Something will catch my eye, and I don’t think about it for very long. I just try to get the shot. By the end of the day I have a phone full of images and more often than not, some of them include homeless people.

On social media like Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, etc., our social lives are constantly being viewed by strangers. We post our pictures voluntarily, or we appear in a friend’s feed in photographs unlikely to offend. But what about taking photos of people at their most vulnerable, and sharing them with strangers?

Dorothea Lange’s photos of migrant workers in the midst of the Great Depression powerfully captured the anguish and resilience in their faces. She empathized deeply with her subjects, and the photos she took for the Farm Security Administration brought the plight of the nation’s poor and downtrodden into the public eye.

I have a similar empathy for the homeless. I find it disheartening to see people sleeping on the ground, or holding up cardboard signs asking for money. However, I am under no illusions that my photographs will ever sway public opinion in the way that Lange’s and countless other photographers have. The question remains: is it ethical to take and publish photos of the homeless?

Some street photographers see themselves as a type of photojournalist or documentarian. Although the lines between these categories can be blurry, I see a distinction. When a news crew photographs the destroyed homes after a tornado or the aftermath of a bomb explosion, there is no question of intent. This is photojournalism. The photographer is reporting an event, and a written story (or a caption, at minimum) typically accompanies the photo. Street photography is different. A street photograph is a self-contained piece of work, with the entire narrative present in that one frame. Words aren’t necessary; the image stands on its own. Photodocumentary falls somewhere between the two. An individual photograph may be striking, but the message that the photographer is trying to convey emerges through a series of photographs. A perfect example of this is Robert Frank’s seminal work “The Americans”. Each of Frank’s individual street images were strong, some more than others. But taken as a collective, the impact was profound, as Frank presented a picture of America that contrasted with the propaganda of the times.

If you’re taking a photo of a homeless person and you’re not a photojournalist doing a news story, or the photo is not part of a specific documentary project, then we’re faced with a question of aesthetics. In other words, can photos of the homeless be considered “art”?

Aesthetically, homeless people look different and live differently from the rest of society. Being homeless is a slice of life that many people are unfamiliar with and never get to see.This makes them interesting photographic subjects. I certainly believe that there can be beauty in the dark side of the world. Ultimately, it’s the individual who decides whether something – in this case, photos of the homeless – is art. Good art induces some kind of reaction in the viewer, however, deliberately photographing something provocative or revolting and declaring it art merely because it generated a strong reaction is unsophisticated and exploitive, and it cheapens the entire genre. Portraying the homeless in photography as some kind of freak show, regardless of how aesthetically compelling it feels, is clearly unethical.

I’m also not totally on board with photographers who say that they are “highlighting the plight” of the homeless or “increasing awareness” of the issue. Many photographers (myself included) fall into this trap when first starting out. Homelessness is nothing new, and the topic has been beaten to death. The world already knows about it (and sadly doesn’t seem to be prioritizing it, especially here in New York City). When Tom Gralish won a Pulitzer Prize in 1986 for his photographs of the homeless in Philadelphia, it truly did bring attention to an issue that was overlooked. The photos were published in a credible publication (The Philadelphia Inquirer) and responsibly shared with the world.

Today, sharing your photos on Facebook and Instagram is a far cry from Life Magazine or a major newspaper. The world isn’t likely to be moved, and social policy changes are unlikely to occur, based on your photo of that homeless guy sleeping on the ground.

Street photographers are artists. We capture images of the world and record social history in a way that is artistic and creative. As a street photographer, I feel like my role is to give testimony to both the beauty and the ugliness of the world. When I go out on a photo shoot, especially in the chaos of New York City, I’m out documenting life on the street as it really occurs. Intermingled with New York’s whimsical and quirky subjects are people who are downtrodden and struggling to get by. If I don’t include them in the collection of photos, am I relaying a false narrative of what’s out there? Does it matter?

Perhaps there is some kind of compromise.

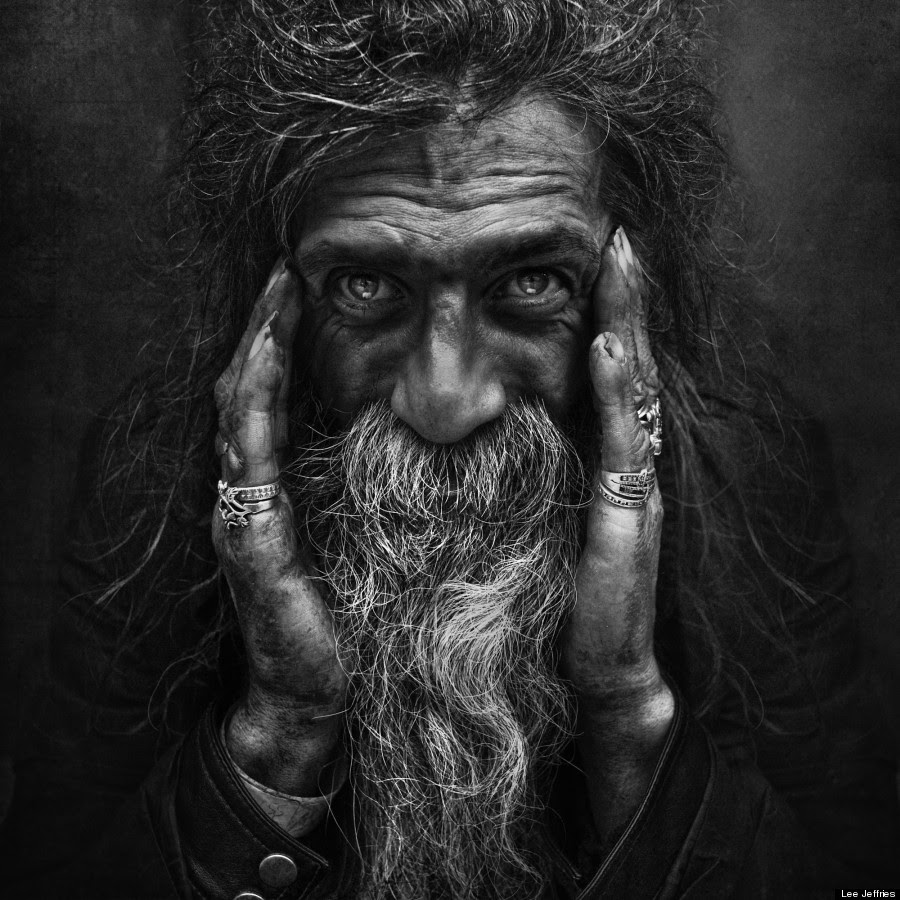

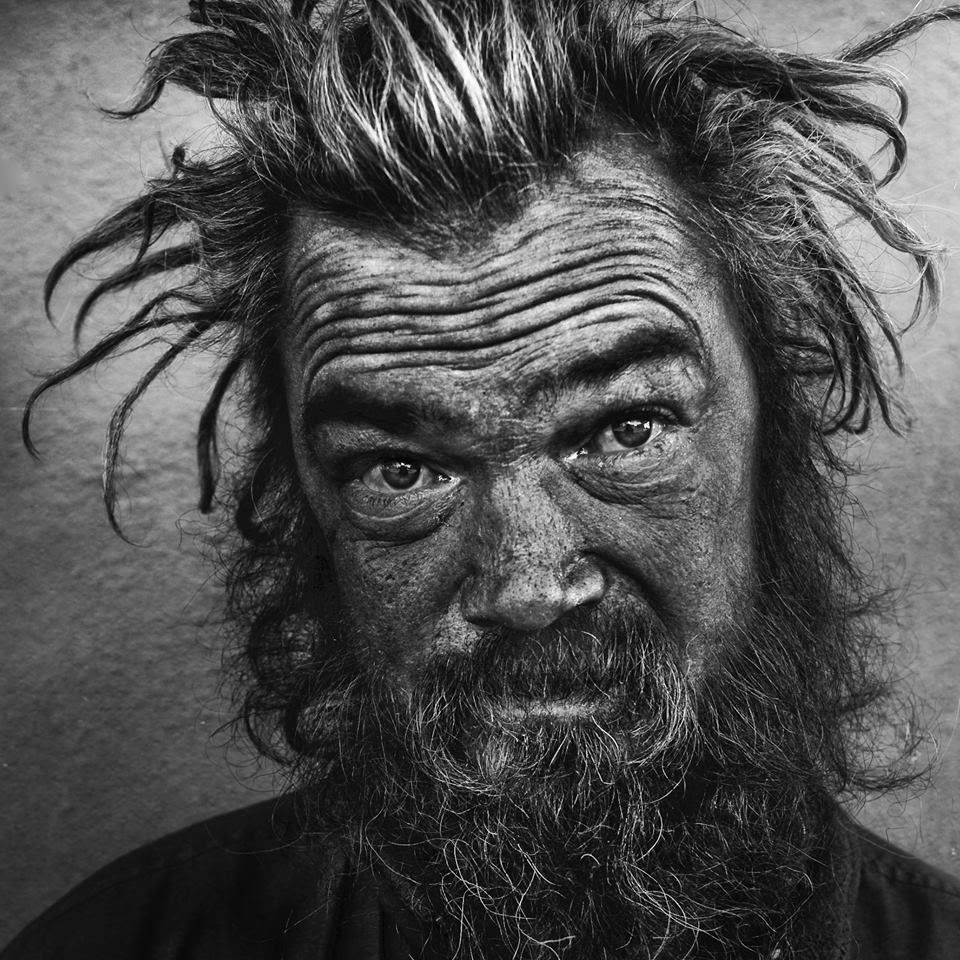

The first amendment of the U.S.Constitution grants people freedom of expression, and the legal right to take photographs in a public space is seen as an extension of this right. If you’re on a public street, you’ve given implicit consent to be observed. For homeless people, however, their consent to be observed really isn’t implicit. They can’t theoretically revoke or decline that consent because they have no place to go. One way around the ethical dilemma is to simply ask permission. However, if your definition of street photography is rigid in the notion that the photos must be candid, then this would compromise that tenet. If you believe that street photography is more about discovering beauty in the mundane, then asking permission would be acceptable. Dorothea Lange’s subjects were leery of her interest in them, but she introduced herself to them, got to know them, heard their stories and earned their trust, and her pictures clearly benefited from it. The photographer Lee Jeffries, upon viewing some photos of a homeless man that he had taken, felt uneasy about it and decided to speak to the man. The man consented to having more photos taken, and these were empathetic, poignant and powerful, forever altering Jeffries’s technique afterward.

Here in New York, I personally would find it difficult to go this route. Although I would find it gratifying to work on a photo-documentary project about the rampant, worsening homelessness in this city and raise money to help those in need, I am not working on such a project, and sadly, I don’t think anyone would be interested in it. My interest in the photos are purely aesthetic, and I suspect this may not be viewed by my subjects as a justifiable reason, if I were asked. There is also the question raised earlier, as to whether a posed photo compromises the definition of street photography.

Another potential compromise: taking photos of the homeless in which their face is obscured. I’ve taken several photos like this. Are ethics an issue if the subject in the photo can’t be identified?

A similar question: is it ethical to take photos of the homeless if the photos are solely for one’s personal portfolio, with no intention to publish them? In this scenario, the photographer only has to answer to himself. If he understands his motives and has made peace with it, then I don’t see the harm, although I waver about this one. There are no easy answers to these questions. Every artist seeks recognition for the art he creates, but I am not driven by a burning desire for fame, and have no interest in earning money from any of my photographs. I’m retired and photography, while a passion, is still just a hobby for me, not a career. I’m not compelled to publish every photo I take, and I’m fine amassing a collection of photos that I find aesthetically appealing and can learn something from but that never see the light of day.

I wrote this blog post with the hope of achieving some clarity on this pressing issue for street photographers, but I seem to have raised more questions than I’ve answered. Ultimately, I believe the ethics of photographing the homeless boils down to intent: what do you hope to achieve by taking the photo? I truly feel that street photography is an art, and if the scene appeals to an artistic aesthetic that fits with your personal style and would be a solid addition to your portfolio, take the photo. With all of my photos, my intent is to humanize my subjects, and this holds especially true for the homeless. In cases where I’m satisfied that I’ve achieved this, I may publish the photo. In cases where I feel I failed and the photo feels more voyeuristic than humanizing, I won’t publish it.