My Trip to Burma: Yangon, Part 1 – Cool Colonial Architecture

We stayed at the Hotel Grand United 21st Street Downtown., located on the edge of Chinatown. Nice hotel, good price, friendly staff. After a restless night (still frazzled a bit from the long flight and lost luggage), we headed up to the 9th floor of the hotel for breakfast. There’s a lovely terrace up there, with nice views over 21st street and Mahabandoola Road, the main stretch. Breakfast was surprisingly varied and tasty, too. I don’t normally eat fried rice and noodles for breakfast, but I adapted quickly. I did snag some toast and jam, and of course, some bacon. And potatoes. And cake. And another piece of cake.

We stayed at the Hotel Grand United 21st Street Downtown., located on the edge of Chinatown. Nice hotel, good price, friendly staff. After a restless night (still frazzled a bit from the long flight and lost luggage), we headed up to the 9th floor of the hotel for breakfast. There’s a lovely terrace up there, with nice views over 21st street and Mahabandoola Road, the main stretch. Breakfast was surprisingly varied and tasty, too. I don’t normally eat fried rice and noodles for breakfast, but I adapted quickly. I did snag some toast and jam, and of course, some bacon. And potatoes. And cake. And another piece of cake. At 8:30, we met with our guide, Myo, and driver, Tarzan. Our incredibly long day of sightseeing, in oppressive, coma-inducing heat, is about to start.

Just south of the church is The Secretariat. Of all the colonial structures in Myanmar, few are as historically important as the Secretariat (also known as the Ministers’ Building), an imposing Victorian complex beyond a barbed wire fence in downtown Yangon. The red brick building at No. 300 Theinbyu Road encompasses an entire city block, sprawling over 16 acres and with covering an area of 37,000 square meters, which is roughly 2/3 the size of the Louvre. This building served as the headquarters for the British-Burma administration during colonial times and later for Myanmar’s independent government. It was here that independence hero Bogyoke Aung San and his colleagues were assassinated in 1947, shortly before the country became a free republic, and where many of Myanmar’s most important Parliament officials worked in the coming years. It is of immense historical significance in Burma. Despite this, the 120-year-old Secretariat, like many buildings of the former capital’s colonial era, now stands in a terrible state. It is currently wrapped in scaffolds and tarps. Restoring this building would be an absolutely monumental task. Al Jazeera described it as “potentially one of the largest historic restoration projects in the world”, likely to cost well over 100 million dollars. I would have given anything to see it up close. In fact, if we didn’t have our tour guide with us, I would have found a way in somehow. There were lots of workers lazily renovating the place, and I think we could have snuck in somehow. From what I could see, it looked majorly impressive.

Always on the lookout for kitties, I spotted this one nearby, as we continued on to our next site, an Armenian Church.

Our next stop was a small church, the Yangon Armenian Church, which dates back to 1863. It is the oldest surviving church in Yangon. It served Yangon’s Armenian trading community who had been there since the 17th century. The land the church was built on was a gift from the King of Burma who had a good relationship with the Armenians of Rangoon. He rewarded them with this piece of land. The church is distinguished by its tropical architecture combined with Gothic features.

As we continued our walk, we passed a guy selling betel leaves. This is something you chew, and it gives you a bit of a buzz, supposedly. Habitual betel chewers are constantly spitting globs of red saliva everywhere, and over time, it turns your teeth a nasty shade of reddish-black. I was curious about it, so our guide treated me to a sample.

Next stop: the famous Strand Hotel. This is downtown Yangon’s hotel to see and be seen in. Opened in 1901, it’s the brainchild of Aviet and Tigran Sarkies, two of the four Armenian Sarkies brothers, an entrepreneurial family who established a string of luxury hotels throughout Southeast Asia including the Raffles in Singapore and the Eastern & Oriental in Penang. Somerset Maugham, Rudyard Kipling, George Orwell, and Lord Mountbatten stayed here. It fell into disrepair following Burmese independence in 1948, but reopened in 1993 after extensive renovations. Elegant teak and marble floors, mahogany and rattan furniture, paddle fans, and the absence of a swimming pool helps preserve the Raj-era ambience and charm. A real treat is to sample this atmosphere over high tea in the famous Strand Café, while listening to the soothing strains of the saung gauk (the traditional Burmese harp). Our guide, Myo, showed us around the colonial-looking lobby, with a glimpse into the dining room and the bar. Also on the premises are a few gift shops and galleries, some of which contained truly lovely items that, if I had more time to browse, would likely have purchased. The Strand Bar is a happening hot-spot, but alas, we won’t be going there tonight. Our flight to Bagan leaves at 6:10 a.m. We have to get up at 4:00 a.m., as our driver is coming to get us at 4:30. There’ll be no drinking or partying tonight, I’m afraid.

Next stop: the famous Strand Hotel. This is downtown Yangon’s hotel to see and be seen in. Opened in 1901, it’s the brainchild of Aviet and Tigran Sarkies, two of the four Armenian Sarkies brothers, an entrepreneurial family who established a string of luxury hotels throughout Southeast Asia including the Raffles in Singapore and the Eastern & Oriental in Penang. Somerset Maugham, Rudyard Kipling, George Orwell, and Lord Mountbatten stayed here. It fell into disrepair following Burmese independence in 1948, but reopened in 1993 after extensive renovations. Elegant teak and marble floors, mahogany and rattan furniture, paddle fans, and the absence of a swimming pool helps preserve the Raj-era ambience and charm. A real treat is to sample this atmosphere over high tea in the famous Strand Café, while listening to the soothing strains of the saung gauk (the traditional Burmese harp). Our guide, Myo, showed us around the colonial-looking lobby, with a glimpse into the dining room and the bar. Also on the premises are a few gift shops and galleries, some of which contained truly lovely items that, if I had more time to browse, would likely have purchased. The Strand Bar is a happening hot-spot, but alas, we won’t be going there tonight. Our flight to Bagan leaves at 6:10 a.m. We have to get up at 4:00 a.m., as our driver is coming to get us at 4:30. There’ll be no drinking or partying tonight, I’m afraid. Not far from the Strand Hotel is the jetty where you catch the ferry to the village of Dalah. Although the village is just across the Yangon River, it might as well be on another planet, as the contrast between the crowded streets of Yangon and the rural landscape of the Delta is supposedly pretty surreal. We didn’t go to Dalah, but we did check out the ferry station, which was pretty hectic.

The ferry station is at the very southern end of Pansodan Street. This was once one of the city’s most prestigious addresses. The street is still lined with impressive old colonial edifices.

Here’s the Customs House, complete with clock and cupola. It’s crumbling and dilapidated, but still a stunner.

Across the street is the Myanma Port Authority building, with its landmark tower and huge arched windows. Note the nice decorations of ships and anchors around the windows.

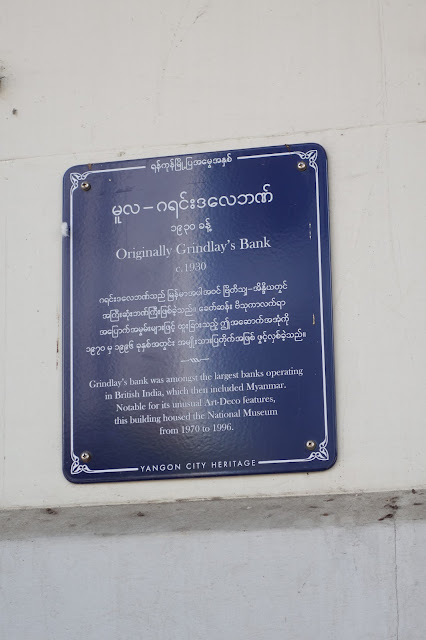

Our survey of colonial architecture continued. We came upon the Ministry of Agriculture and Irrigation, with its solid-looking vaulted gold doors and fancy silver canopy. This used to be the Yangon branch of Grindlay’s Bank. It was turned into a national museum in 1970. In 1996, the building returned to its banking status and becomes a branch office of the Myanmar Industrial Development Bank, which operates under the Ministry of Agriculture and Irrigation.

Our survey of colonial architecture continued. We came upon the Ministry of Agriculture and Irrigation, with its solid-looking vaulted gold doors and fancy silver canopy. This used to be the Yangon branch of Grindlay’s Bank. It was turned into a national museum in 1970. In 1996, the building returned to its banking status and becomes a branch office of the Myanmar Industrial Development Bank, which operates under the Ministry of Agriculture and Irrigation.

At the junction of Pansodan and Merchant Street is the chintzy Lokanat Building, also known as Sofaer’s building. It was built in 1906 by Isaac and Meyer Sofaer, Jewish brothers born in Baghdad and educated in Rangoon. This building was the epicenter of city life. The Reuters telegram office was here, and there were shops selling German beer, Scottish whisky, Egyptian cigarettes, and English sweets.

At the junction of Pansodan and Merchant Street is the chintzy Lokanat Building, also known as Sofaer’s building. It was built in 1906 by Isaac and Meyer Sofaer, Jewish brothers born in Baghdad and educated in Rangoon. This building was the epicenter of city life. The Reuters telegram office was here, and there were shops selling German beer, Scottish whisky, Egyptian cigarettes, and English sweets. Looking north from the park, you see the sky-blue City Hall. Built in several stages from 1925 to 1940, it was among the first large buildings to use a hybrid style that combines European design with traditional Burmese flourishes, like the pagoda-topped roofs, stone latticework, and peacocks. City Hall is the site of several major historical events. After the defeat of the Japanese in 1945, the Rangoon War Criminal Trial opened on March 22, 1946 and was held here; City Hall was converted into a courtroom. General Aung San (Aung San Suu Kyi’s father) made his last public speech on the balcony here on July 13, 1947, only 6 days before he was assassinated. City Hall is a major focal point for political demonstrations.

Looking north from the park, you see the sky-blue City Hall. Built in several stages from 1925 to 1940, it was among the first large buildings to use a hybrid style that combines European design with traditional Burmese flourishes, like the pagoda-topped roofs, stone latticework, and peacocks. City Hall is the site of several major historical events. After the defeat of the Japanese in 1945, the Rangoon War Criminal Trial opened on March 22, 1946 and was held here; City Hall was converted into a courtroom. General Aung San (Aung San Suu Kyi’s father) made his last public speech on the balcony here on July 13, 1947, only 6 days before he was assassinated. City Hall is a major focal point for political demonstrations.Our next destination was the principle tourist attraction in the city. It’s commonly called Scott Market (after the municipal commissioner at the time it was built) although it’s officially known as Bogyoke Market, or Bogyoke Aung San Market. It is home to Burma’s most diverse and tourist friendly collection of souvenir shops. You can buy just about any kind of junk you desire here. Jade, lacquerware, paintings, and clothing. The main alleyway through the center of the market is lined with dozens of jewelers selling gold, silver, emeralds, and jade jade jade. Built in 1926, it was renamed Bogyoke (“General”) Aung San Market after the country’s beloved independence leader in 1948. The market was busy, but not insane like the Bin Tay and Ben Thanh markets in Saigon. If we weren’t with a guide, I would have probably done more shopping. I did manage to snag a t-shirt for my buddy Brad.

In one of the storefronts at the base of these buildings, I spotted an unthrifty-looking kitten (clearly has conjunctivitis), and a cat who looks related. It’s frustrating that I can’t treat that little kitten. A few eye drops in the right eye would fix that right up.

It looks like we covered a lot, but that was just the morning! In my next post, I’ll show you the two big pagodas in town (the Sule and the Botataung), and then we’ll go north of the city to see two huge, prominent Buddhas, before the star attraction – the Shwedagon.