Amsterdam and Paris 2015 – Part 1 – Arrival

I love to travel. It’s what I live for. Although I tend to seek out new and exotic lands, it’s nice to go back to familiar places now and then. I get to revisit restaurants and museums that I enjoyed the first time I visited, and I get to check out new neighborhoods, new exhibits, and new shops and stores. So, for my first trip of 2015, I chose two fantastic cities – Amsterdam and Paris. As you know, I’m a cat veterinarian and enthusiast, so I try my best to do and see anything that may be cat-related while I travel. Previous trips I’ve taken – to Greece, Turkey, and Morocco – made this easy. These countries were swarming with stray cats. They were everywhere. This is not the case in Amsterdam and Paris, however, I did manage to see a few, as you’ll soon discover.

We (Mark and I) arrived in Amsterdam on a Wednesday afternoon. I have the good fortune of having a close friend who happens to live right in the heart of Amsterdam, so we stay with him.

Here’s what you see when you look down the street, to the left.

This was my third visit to Amsterdam, and Mark’s second. I knew the layout of the city pretty well, so with map in hand (just in case), we hit the streets for a few hours.

You can understand why I keep coming back to this city. Just look at how lovely this place is. The canals, the boats, the canal-side homes… just beautiful.

As we walked south along the Singel canal, we soon came upon a little plaza featuring a statue of Multatuli.

For non-Dutch folks, the name Multatuli probably means nothing. But I had just finished reading Russell Shorto’s wonderful book Amsterdam: A History of the World’s Most Liberal City (which I highly, highly recommend), so I’ve been clued in. Rather than digress into his story, I’ll save it for the end of this blog post.

We continued past the statue and just strolled the streets.

I saw this sign, which I found amusing, because the bottom of the sign looks like it’s pointing to Adam West, who played Batman on the TV series.

As we strolled past a cafe, I spotted this kitty beneath one of the outdoor tables.

The XXX is the symbol of Amsterdam. You can spot the three X’s on the coat of arms that is frequently seen on buildings and monuments in Amsterdam. They are silver St. Andrew’s Crosses, also known as saltires, the type of cross on which St. Andrew is said to have been crucified. They are a common heraldic symbol worldwide. We decided to go into the cafe and get a bite and a drink. I ordered hot chocolate with whipped cream. Rather than put the whipped cream directly on the hot chocolate, they put it on a little plate that rests on the top of the glass. We walked along the Singel canal, admiring the view.

At the crossroad, there was a herring stand, and Mark ordered the raw herring, which they top with onions and pickles. The herring is cut into small pieces, which you eat with a toothpick that has a Netherlands flag on it. I find the herring completely gross, but Mark loves it.

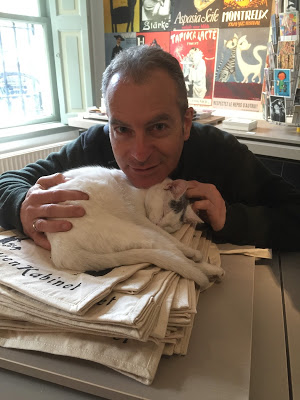

We then strolled along the Golden Curve (a stretch of beautiful, upscale canal houses). The Golden curve found along the Herengracht canal. This is a very upscale part of the city. On this stretch of canal, the governors of the East India Company used to live. In the 1660’s, these opulent homes lined the cobbled streets, flanked by elm trees. No two homes looked alike. The Herengracht is the most “noble” canal in Amsterdam, and this is the most elegant part of it. We came across Katten Kabinet, the museum of all things cat-related.

I went there five years ago (and briefly popped in two years ago). At both visits, there was a sweet old cat that lived in the museum. I asked the woman at the ticket desk if that cat was still alive, and sadly, she said that the cat had passed away. But in the gift shop, there was another resident cat who I guess was taking her place.

She was napping, but enjoyed the attention I gave her.

We continued our trek through the southern canals, and strolled past the National Opera House.

It’s located at a bend of the Amstel River on a plot of land called Vlooienburg, between Waterlooplein Square and the Zwanenburgwal Canal. The building is shaped like a huge block, with a curved front that faces the city. The curved facade of the theater is covered with white marble, punctuated with large windows that give great panoramic views of the river.

Our wanderings took us to the southern canals, which was a bit quieter. Here’s Mark looking over the Amstel canal. What’s he looking at? The Skinny Bridge!

Like Venice, Amsterdam and water are practically synonymous. The city has over 1250 bridges, the most well known being the Magere Brug, which translates literally as the “Skinny Bridge”. It spans the Amstel, connecting Kerkstraat with Nieuwe Kerkstraat.

In 1691, a bridge was built here. It was named Kerkstraatbrug, and it was said to be so narrow that the locals named it the skinny bridge. Legend has it that the bridge was built by 2 sisters who lived on opposite sides of the river. The bridge was completely rebuilt in 1871 and again in 1934 – with the last major renovation in 1969. Today only pedestrians and bicycles are allowed to cross. No cars.

A few of the cables have “love locks” attached, a tradition that I’ve always found romantic and charming.

Here’s a view from the south side of the drawbridge, looking north. So charming.

I spotted a cat cautiously venturing out from the restaurant where he resided. The street was quiet, and after peeking around the street, he lazily ambled back into the restaurant.

Dinner was at a restaurant away from the city center, on the other side of the city, Amsterdam-Noord (North). A trendy, elevated restaurant called REM. It used to be a 1960’s pirate TV station. It kind of looks like a miniature oil rig.

It is now positioned in the waters of the Houthhaven. You get to experience elevated dining with aquatic views of the southern shoreline, and panoramic views of the Noordzee Kanaal. Pretty cool looking building.

By this time, we had been awake for about 30 hours, so it was time to head back and hit the sack. But before I leave you, here’s what you should know about Multatuli.

In the mid-19th century, the guy represented in the statue below was quite well-known in Europe and America, and in 2002 the Society for Dutch Literature declared Eduard Douwes Dekker, who wrote under the pen name Multatuli, to be the most important Dutch writer of all time. His works ignited international upheaval that still echoes today. His parents sent him to school to be a minister, but Eduard would have nothing of it, so when he was 18, his parents put him on a vessel bound for the Dutch possessions in the East Indies, hoping he would makes something of himself in the colonies. When he arrived in the archipelago in 1838, he fit right in, working his way up from a clerk in Jakarta to district officer in Natal, in western Sumatra. As he experienced the exploitation of peasants, he started to become indignant and became something of a whistle-blower. He often took the side of a local resident against the Dutch. He was something of a hothead, though. He was devoted to his work, but really erratic in his behavior. He would get commended and promoted, but also would get into fights. He was even suspended for a year for irregularities in his accounting. He became a gambler. He fell in love with a Dutch girl and converted to Roman Catholicism to appease her and her parents, but she broke it off when her father told the girl that Eduard had a bad reputation. Later, on a vacation to Europe, Dekker gave much of his money to a French prostitute to enable her to leave her profession, and then lost the rest of his money at roulette. He went back to the prostitute and asked for his money back. She gave it back! In 1856 Dekker was transferred to Java Island, where he was second in command in the province of Bantam. As he read through the paperwork left behind by his predecessor, he discovered that the man had been documenting the terrible exploitation of the people by the Indonesioan overlords, with the complicity of the Dutch. He became enraged and in only a few weeks, he launched a public inquiry into the conduct of the Javanese nobleman in charge of the area, a guy named Karta Nata Negara, who held the Dutch title of “regent”. He charged the regent with extortion and systematic abuse and demanded that the resident (his immediate Dutch superior), take action. When he refused, Eduard went to the governor-general of the whole colony. He too refused to do anything, so Eduard resigned his position and went back to the Netherlands to try to make the Dutch aware of the abuse taking place within their system. Back in Europe, in a blaze of creativity and inspiration, he produced the book that would make him famous, Max Havelaar, a fictionalized account of his stay in the East Indies. Eduard Dekker chose the histrionic pseudonym Multatuli (which is latin for “I have suffered much”), and the book became a sensation. It became an instant bestseller and was translated and read around Europe. It echoed around the Dutch government, and really had an impact on the Dutch populace. For the first time, many Europeans saw that their relatively comfortable lives were built on the misery of people in faraway places. The Dutch realized the irony – that they were doing to the Indonesians what the beleaguered Spanish empire had done to them (which had led to their own revolution and independence). The British loved the book, because it highlighted the inhumanity of the Dutch colonial system. The first English edition of Max Havelaar appeared in 1868, and it compared it to Uncle Tom’s Cabin for the way it awakened a society to its systemic abuse of a whole people.

To make a long tale a little shorter… Multatuli capitalized on the fame of his book by writing others that promoted issues he was passionate about, mainly social liberal issues. He took on voting rights (insisting that all males be able to vote, and not just those who earned a certain income and paid a certain amount of taxes). His appeal expanded to include women. Then he championed workers’ rights. He also took on established religion. He was a passionate atheist who believed that education should have the objective of weaning people off religion and leading them to use their powers of reason. The secular movement that was just in its infancy in Europe began to take off even more, thanks to Multatuli’s writings. He became the darling of pretty much all activists, and he was a vital presence in virtually every important cause of his time, especially the anti-colonial cause. The book Max Havelaar wasn’t written specifically to bring down the colonial system, but that’s what it eventually ended up doing. So if you visit Amsterdam and come across this statue, tip your hat to the guy, because he’s really a hero. His influence helped make Amsterdam the great liberal country that it is.

Trip Continued – Day 2: HERE