White Dopes On Punk

Call me particular, but I like to listen to music when I spay a cat. Having a live band in the operating room would be impractical, but through the miracle of the interwebs, I can listen to anything I like these days. Perusing the playlists on Songza is one of life’s simple pleasures, although choosing a playlist can be challenging. Today is August 27, Neil’s birthday. I’ve been feeling nostalgic, so picking today’s playlist is easy: “Up Yours! Punk Songs of Defiance”. I click “play”, and the first notes of Alternative Ulster by Stiff Little Fingers blast from the speakers. I am transported.

Summer, 1977. At John Dewey High School, I hung with “The Freaks”. Like most teenagers, my worldview was expressed through the music my friends and I listened to, and in our world, The Kinks, The Who, Jethro Tull, Yes, Emerson, Lake & Palmer, Pink Floyd, The Stones, Led Zeppelin, Kansas, Queen, Elton John, Neil Young, Bob Dylan, and Bruce Springsteen reigned supreme. Unlike our rivals “The Hitters”, we despised disco and everything it represented. Our drug of choice was pot, and we smoked it in massive amounts. Donna Summer, Chic, The Bee Gees and their ilk were anathema to us. Pure poison. We kept our hair long, sewed peace-symbol patches on our clothes, and affixed rock star iron-ons to our t-shirts. We wore our freak flags proudly.

Brooklyn was our habitat, and during the week we were aware of little else beyond its borders. The weekends were a different story. In 1970s Brooklyn, mundane was the order of the day. The true adventures took place in “the city”, and one little subway token was our ticket to the decadent playground to the north.

Danny, the freakiest of The Freaks, was also our principal supplier of weed. One Friday night, Danny had ventured to the Waverly Theater (now the IFC Theater) to finally discover exactly what the Rocky Horror Picture Show was all about. We had all seen the small, cryptic ad for it in the Village Voice, the title written in a drippy red font, with the slogan “A Different Set of Jaws”. The Monday after, Danny regaled us with tales of a sweet transvestite, his bizarre servants, and an intense soundtrack. He implored us to join him again the following Friday. Danny described the audience participation during the film, and emphasized that the air in the Waverly balcony was thick with pot smoke. We had been curious already. The pot smoke sealed the deal. We made plans to attend the following Friday.

The eccentrics present at the Waverly were considerably stranger than the characters in the film. Most memorable was Thomas the Mortician, a moviegoer we met while waiting in line outside the theater. British, black, and in his ancient late 20’s, he could not have been more different from us white kids from Brooklyn. This was an asset. We were The Freaks, and anything or anyone subversive or non-mainstream drew us like a magnet. Thomas, an actual mortician by vocation, was welcomed into our crowd instantly.

One warm summer Friday evening, we claimed our usual early place on line outside the Waverly box office. The movie line eventually snaked around the block by 11:45. Thomas joined us in line. He was in rare form, dressed in his in best Frank-N-Furter leather-and-eyeliner regalia. I asked about the fake blood on each of his fingers, and he assured me that it was anything but fake. “I am a mortician, remember”, he said. The conversation shifted (thankfully) to music, and he began raving about the Sex Pistols, blithely assuming I was familiar with them. I had heard rumblings about them, but really knew very little, and I confessed as much. Thomas reacted with shock and dismay. “Come with me, young man”, he said with dramatic British flair. He grabbed me by the arm and marched us both straight into Bleecker Bob’s on the corner of MacDougal and 8th where, for $3, he purchased the vinyl 45 of “Anarchy in the U.K.” as casually as if he were buying a muffin. “After the movie tonight, you take this home, and you play it loud”, he said. “Trust me, your life will never be the same.” I obeyed.

My conversion from “Freak” to “Punk” was instantaneous. I now had a dilemma: how to break this to my fellow Freaks. They would be unlikely to take it well, as our initial stance on punk was not very different from our mindset about disco. My migration from “Carry on My Wayward Son” to “God Save the Queen” was abrupt. Thomas the Mortician was correct. I’d been to Oz. There was no going back to Kansas.

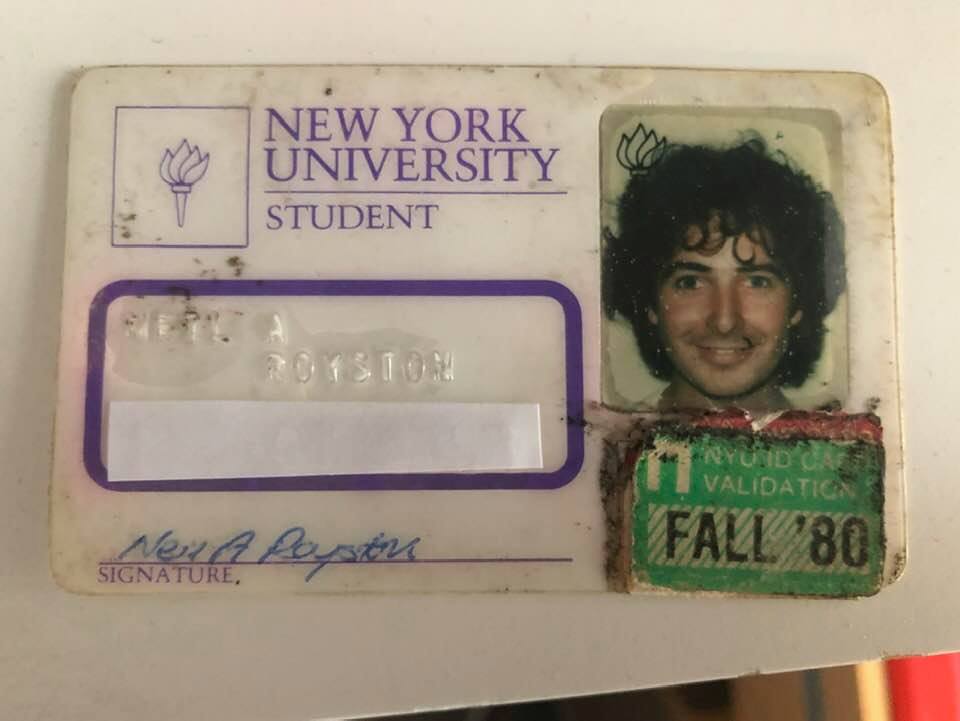

As the last weeks of June approached, the trauma of high school ending and college beginning was upon me. Most of my fellow Freaks were juniors. Ever the overachiever, I had skipped from seventh grade directly to ninth, and was one year ahead of my friends. Though I craved the classic college experience — the campus, the dining hall, the dorm parties, the ivy-covered buildings — I wasn’t ready to leave my high school clique. Danny and Dave, Ellen and Jamie, Luke, Chuck, John and Pam were more than friends; they were my family, my peeps, my posse. My new love for punk music notwithstanding, these folks understood me, and I understood them, and with them I felt safe and loved. Though I pondered applying to upstate or out-of-state colleges, I chose not to. I couldn’t bear the thought of leaving. When I got accepted to New York University, I breathed a sigh of relief. Come September, I’d still be taking the subway to school. My weekdays would be different, but the weekends would still be ours together.

With my sights set on being a veterinarian, my NYU curriculum was heavy in science, with a dose of liberal arts thrown in for good measure. My pre-veterinary first semester schedule included inorganic chemistry, calculus, and the de rigueur Psych 101. The psychology class was very popular, and the massive auditorium was filled to capacity for the lectures. The class was split into smaller discussion groups that met weekly in a basement classroom in one of the brownstones bordering Washington Square Park.

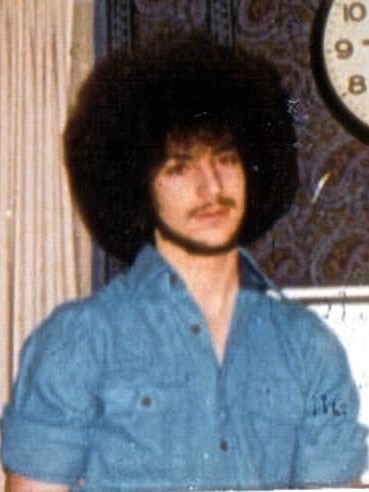

One afternoon, our study group was reviewing an assignment given to us the day before. After reading a chapter in the textbook, we had to answer a few multiple-choice questions, some of which, we were warned, could end up on the midterm exam. Our teaching assistant asked if anyone had difficulties with any questions. Our chairs and desks were arranged in a circle, and the guy sitting to my left quickly spoke up. He was short — maybe 5’6” — slightly pudgy, with a mop of wavy dark hair, dark brown eyes, a permanent five o’clock shadow, and phosphorescent skin that had seen very little sunlight. “I couldn’t quite figure out the answer to question six”, he said, in a posh British accent. “Is it ‘Pavlovian’, ‘Skinnerian’, ‘nature’, or ‘nurture’?” It was the simplest of all the questions, and I thought to myself that this guy must be an idiot. As the session came to a close and we shut our notebooks, I glanced over at his desk. Scrawled on the outside cover of his spiral notebook, in messy, juvenile penmanship, were the names of the ranking British punk bands of the day: The Sex Pistols, The Clash, Generation X, The Jam, The Stranglers, and X-Ray Spex. Some were just the written names. Others were poorly drawn band logos. My opinion instantly changed. Amazed that I had found a kindred spirit, I pointed to his book and declared that I liked those bands as well. His eyes lit up immediately.

“Really! I’m British, you know”, he exclaimed.

I rolled my eyes. “No shit, Sherlock”, I said. “Have you been to Bleecker Bob’s yet?”

“No, what’s that?”

I asked if he had any other classes that day. He didn’t, and neither did I. “Let me take you to Bleecker Bob’s”, I told him. “It’s the best store in the city for punk records, and it’s only five minutes from here.” And then, “I’m Arnie, by the way”.

“I’m Neil”, he said. “Arnie. Is that short for Arnold?” Yes, I told him. Yes it is.

We headed over to 8th Street, turned onto MacDougal, and pushed the door open. As the sound of The Buzzcocks hit our ears and the punk posters came into view, Neil nearly fainted from the head rush. Most New Yorkers remember Bleecker Bob’s as the spacious store on West 3rd Street, but few people recall its modestly sized prior incarnation, on MacDougal Street. It was a narrow space with high ceilings. The sales counter was on the left, and ran most of the length of the store. Upon entering, your eyes focused on the wall immediately behind the counter section nearest the door. This area was Punk Central, where the newest records of the day were displayed in their picture sleeves, high upon the wall. Every square inch of that wall was adorned with LPs and 45s. The rest of the store had punk t-shirts, buttons (“badges”, Neil admonished me), posters, and books. Behind the counter was Bleecker Bob himself, along with his menacing Doberman.

Neil was absolutely floored. He was new to New York, and he could not believe that a store like this existed here. He had been lamenting the timing of his family’s relocation here just as punk was breaking in the U.K., and had been feeling increasingly detached from London. Now in Bleecker Bob’s, he felt reconnected. I had been coming here for months, ever since Thomas bought me the Anarchy in the U.K. single. I already knew that this was punk Mecca. It was great having a fellow disciple to accompany me.

In no time, we were regulars, visiting Bleecker Bob’s almost every day. Mostly we went to check out the latest records, but in a perverse way, we also hoped to witness Bob in prime form. Bleecker Bob and his Doberman were equally adept at barking threats of violence at the customers, though if I had to put my money on one of them, I’d go with Bob. More than once we witnessed Bob toss someone out of the store for transgressions as minor as a disparaging comment about a band Bob liked, or a complaint about a price. He was the Soup Nazi for records. He ended up liking Neil and I though, probably because he could see how much we valued being in his shop. (Neil dropping hundreds of dollars there didn’t hurt.) In fact, during one sojourn to his store, Bob was so enamored with the British-made coat that Neil wore into the store that he pleaded with Neil to sell it to him on the spot. Neil demurred, and Bob offered Neil anything in the store. Neil politely declined again, and Bob eventually stopped asking. If Bob had threatened banishment from the store, he’d probably be wearing that coat today.

Neil and I became close friends. Soon after we met, I asked him if he smoked pot. He said no, but that he had always wanted to try it. He admitted that more than once he came close to buying some from the dealers on the western edge of Washington Square Park. “Don’t go there unless you’re into smoking oregano”, I warned him. (I had learned this the hard way, sadly.) I said that I could get some pot easily. We made plans to get stoned the following week. I got some excellent weed (thank you, Danny) and the next week, between classes, we went to a less-trafficked corner of Washington Square Park and smoked a fat joint. For lunch, we hit NYU’s Rathskellar. We nestled into a small booth and ordered your standard American lunch: a hamburger, fries, and a Coke. The weed was strong, and Neil’s virgin brain was definitely feeling it. He marveled at the deep shade of green of the vegetation on his burger, regretting that he had never noticed the vibrancy of Romaine lettuce. He discovered he could draw alphabet letters using the red plastic squeezable ketchup bottle. “Watch this!”, he said, as he tried reproducing The Jam logo on his burger in ketchup. Instantly, his sleeve was covered in red goo, causing him to laugh deliriously. “This is bloody amazing”, he said, biting his burger. Beef juice dribbled down his chin. “Wipe your face! Jesus Christ!” I said, throwing him a napkin. The Rathskellar had a jukebox in the corner, and through the lunchroom din we could hear Night Fever by The Bee Gees, soon followed by Stayin’ Alive. I acknowledged the music and groaned. “We’ve got to put a stop to this”, Neil exclaimed with newfound boldness. “I’ll be right back”, he said, as he traipsed across the room. We had no idea what other records were in the jukebox, but I guarded our table while Neil pumped in the quarters. He hurried back. In a minute, the opening chords of Anarchy in the U.K. filled the air. I grinned. “Anarchy was on the jukebox?! Good work!”, I said. Unfortunately, a collective groan arose from a group of disco-boys and their girlfriends seated at a table near the jukebox. Of course, this made our selection perversely more satisfying. Midway through Anarchy, one of the guys bumped the jukebox deliberately, and Johnny Rotten’s lovely tenor abruptly vanished. The disco-boys laughed, as The Bee Gees came back on. I winced. “Fear not, young Arnold”, said Neil. Soon enough, Mr. Rotten was back for an encore. “Again?”, I asked. “I put in eight quarters”, Neil said, smiling. “It should come on six more times.” The disco-boys and their women left in disgust. We got dessert and stayed for all six playings.

Our friendship quickly morphed into a mutual admiration society. I’d been an early fan of Monty Python’s Flying Circus, watching each episode with fascination every Sunday night at 10:00 p.m. on Channel 13, the PBS station. The British were more liberal when it came to television, and for a teenager, the random frontal nudity was shocking. While I certainly didn’t grasp every reference or colloquialism in the show, I was sharper than most kids and I understood most of it. I became a budding Anglophile at age 15, besotted with all things British. Having an actual British friend in the flesh seriously boosted my street cred. I bombarded him with questions about all of the Britishisms I didn’t comprehend, which he answered with great amusement. Yes, fries are chips, and chips are crisps, he confirmed, rolling his eyes. I also made fun of his accent mercilessly, like Lucy did to Ricky. He retaliated by pitifully trying to imitate my Brooklyn accent, which, although nearly gone now, was much stronger then. His British-Brooklynese dialect was more amusing than any Monty Python skit. Much of his mimicry involved the use of the adjective “fuckin’” before nearly every noun, a persistent vice of mine. I tormented him for saying “vittamin” instead of “vitamin”, and he rode me about my incessant use of “gimme” and “gonna”. I was vicious when we passed a Sabrett hot-dog stand in Central Park and he asked me, “What’s a knish?”, mispronouncing it as “nish”. “The k isn’t silent, dipshit”, I said to him. “You’re a fuckin’ Jew! How can you not know what a knish is?!” (I’m a tribe member myself, by the way.) He responded, “Listen, toss, they don’t have KUH-nishes in London”. Trading insults comes natural to teens, and we reveled in it. My American epithets were immediately countered by him, his main reprisals being “wanker” and “toss-pot”, which he frequently shortened to “toss” or “tosser”.

Although punk was exploding in New York City and the bands here were amazing, we both were partial to the English punk bands. It was agonizing for him to not be back in London to experience it. He was grateful that I was as interested in the music as he was. Music was our primary bond, and we pursued it with unbridled passion. We listened to scores of punk bands and pounced on any tidbits of band information we could find. The Clash, The Sex Pistols, The Stranglers, The Jam, XTC, The Buzzcocks, X-ray Spex, The Slits, The Adverts, Generation X, Joy Division, Alternative TV, Eater, The Damned, Ian Dury, The Members, Sham 69, Siouxsie and the Banshees, The Fall, Ultravox, Wire… you name ’em, we were into ’em. This isn’t to imply that we didn’t like American punk. We were crazy about it. The Ramones, Patti Smith, Television, Talking Heads, Blondie, Suicide, Richard Hell and the Voidoids, The Dead Boys…we submerged ourselves in it. We ate it, drank it, breathed it. We listened to Chelsea, The Cramps, and The Ruts. We listened to the Anti-Nowhere league, The Saints, and the U.K. Subs. If WNEW deejay Meg Griffin played it on her show, we went out and bought it the next day. Although we gravitated to the most popular bands, lesser-known bands did not get snubbed. If it was loud and had attitude, we listened.

Though I went to school in the city, I still lived in Brooklyn, and the majority of my school nights were spent studying at home. Neil didn’t care about school, and he couldn’t be bothered to study. He preferred skipping class, spending his time in the many local record shops, chatting with the proprietors, and staying on the cutting edge, which he then shared with me. In addition to punk, he introduced me a whole new world of reggae and dub artists, as this genre was gaining popularity amongst punk musicians and fans. We spent many inebriated hours listening to King Tubby, Dr. Alimantado, Michigan & Smiley, and Augustus Pablo. We smoked dope and listened to Scientist. We inhaled nitrous oxide and listened to “Hamburger Lady” by Throbbing Gristle. We wore out the grooves to Culture’s “Two Sevens Clash”. It was new and it was cool and it was interesting and we loved it. There was no YouTube, no Pandora, no Napster, no Spotify. If you wanted to hear the music, you had to buy it. Fortunately, Neil’s family was rather well-to-do, and he had the means to buy the records I only could drool over. He casually purchased PiL’s Metal Box, in the original cumbersome metal canister. He had the cash for picture discs and colored vinyl. While others desperately yearned to hear the exorbitantly-priced rare Capital Radio single by the The Clash, or The Buzzcocks’ elusive Spiral Scratch EP, Neil nonchalantly bought them at Bleecker Bob’s. I, the broke NYU student, was the lucky beneficiary, borrowing and taping them all on cassettes (which I still have.)

For Labor Day that year, Neil invited me out to his home in Great Neck. I knew Neil had told his family about the punk-loving American friend that he met at NYU, and I was concerned that his snooty upper class family might accuse me of abetting their son’s indulgence in that “horrible offensive noise” that Neil played on his stereo every waking moment. But I was dying to see how the other half lived, and I accepted the invitation immediately. I took the LIRR to Great Neck, where I was met at the station by Neil. We strolled to the parking lot. I was expecting to see Neil’s modest little Pontiac Sunbird, but instead, he led me to rather opulent car. I can’t recall the make or model, but it to me it was a hotel on wheels. “You traded in your Sunbird?”, I joked. “It’s dad’s car. I should have had his driver pick you up, just for a laugh”, he said.

Neil’s home was palatial. I entered the foyer, and then the living room, where the majority of the far wall was comprised of a window that looked out onto the Long Island Sound. A smartly dressed woman entered the room and headed right for us. “Mum”, said Neil, “this is Arnie”. She extended her hand. “Ah, yes. I’ve heard a lot about you. You’re studying to be a veterinarian, is that right?” I told her yes, it had been my lifelong dream. “Good”, she said. “Maybe some of that ambition will rub off on Neil here.” Neil grimaced. “Come on up to my room”, said Neil. I ascended the staircase at the far end of the living room, to the second floor of the house. As we headed down the hallway toward Neil’s room, I envisioned a room covered in punk posters, records scattered everywhere, not unlike my own. Instead, the room was pristine, with a neatly made queen-sized bed and décor straight out of Architectural Digest. Neil registered my surprise. He explained that his mother insisted he keep his room tidy and decorated nicely. He said that their maid vigorously enforced the law. “Check this out”, he said, as opened a door on the far wall. It was his massive walk-in closet. I peeked inside. The entire wall was a collage of punk posters and crudely cut up pictures from punk magazines. “Guests don’t see it, so mum doesn’t care”, he said. The real Neil was hidden in the closet. I understood that fully, but more on that later.

In very un-punk fashion, I took my schooling seriously. The only thing that surpassed my love of punk was my love of animals, and I focused on becoming a veterinarian. Weeknights were devoted to schoolwork. Weekends were devoted to punk.

The months that followed were a blur of concerts, clubs, bars, and parties. Neil and I were fortunate to be in the right place — New York City — at the right time, and we saw some great gigs: The Cramps at Irving Plaza, The Jam at CBGB’s short-lived Second Avenue Theater, The Stranglers at the Entermedia Theater, The Tom Robinson Band at the Bottom Line, a very scary Nick Cave and The Bad Seeds at Danceteria, Stiff Little Fingers at the Peppermint Lounge, The Buzzcocks (with Gang of Four opening!) at My Father’s Place, and countless others.

One afternoon, we were having lunch in the McDonalds on the corner of West 3rd and 6th Avenue, when a guy ambled over with a cigarette in his mouth and asked for a light. We immediately recognized him. It was Richard Hell. Holy shit! Neil dropped his burger and said, “Um, no, sorry”. I said, “Sorry, we don’t smoke.” Hell drifted away. Neil threw a French fry at me. “Why did you tell him we don’t smoke?!” he said, flustered. “Because we don’t!”, I said. “Yeah, but it made us look totally uncool”, he said testily. “Oh please, get over it”, I said. After we left McDonalds, Neil went right to a nearby bodega and bought a Bic lighter. “You’re buying a lighter?” He said, “The next time Richard Hell asks me for a light, I’m going to be prepared.”

Despite all the concerts and partying, I remained committed to my studies. The career track for veterinary medicine has always been intensely competitive. Commuting to NYU from Brooklyn was easy enough, but living at home with my parents taxing. I couldn’t study in peace, and I felt increasingly smothered at home. It was time for me to finally sever the apron strings. The Freaks had all moved on to their respective colleges, or elected not to go to college at all, and we were losing touch with each other. Still yearning for the true college experience, I transferred to SUNY Binghamton in the fall of 1978. The move to Binghamton was a positive one for me, academically and socially, although it caused Neil and I to drift apart a little. Although I was only four hours away, it felt as if I had moved to another country. We kept in touch with phone calls and letters, and hung out when I came back home for summers and holidays, but already we had started living in different worlds.

Sophomore year at Binghamton was huge. I had acquired a tight circle of close friends, and even experienced first love. As summer approached, it pained me to say goodbye to my Binghamton friends. However, I was delighted to be back in the city for a few months, and to reconnect with Neil and my former Freaks. The summer of 1979 was warm and crazy, and Neil and I got right back into our groove. One night in particular stands out above all others. Neil and I had just finished seeing a weeknight performance by The Psychedelic Furs at The Ritz (now Webster Hall). The show started around midnight and ended at 3:00 a.m. We floated back to Neil’s apartment, and still hyped up from the concert, decided to put on some reggae, do a few bong hits, and just chill before eventually crashing. On Neil’s coffee table was the Village Voice, our most vital resource for listings of who was playing at CBGBs, Max’s, Irving Plaza and Danceteria. Flipping through the film ads, I saw that the 8th Street Playhouse was having a “Rock All Night” movie festival. At midnight, they showed The Song Remains the Same. At 2:00 a.m.: Jimi Plays Berkeley. At 4:00 a.m. they would be showing Quadrophenia, and at 6:00 a.m., The Kids are Alright. I checked my watch. It was almost 4:00 a.m. We hurried our last bong hit and zoomed out of Neil’s apartment. Neil’s fabulous studio at the Brevoort East on 9th Street and 5th avenue was thankfully only a block and a half away. We didn’t know what type of crowd, if any, would be in a movie theater on a summer weeknight at 4:00 a.m. To our disbelief and delight, the theater was packed to capacity! We managed to find two seats together just as the Quadrophenia credits began. Neil had been back to England two or three times to visit friends since he arrived here in ’77. Upon returning to NYC, he’d be glum for a week or two. He still felt that he was missing out on the amazing U.K. music scene, but it went deeper than that. He felt exiled, banished, forced to leave England against his will. Now, as he watched Quadrophenia in New York City, surrounded by a bevy of admiring anglophile peers, his longing was replaced by pride, as the totally dope depiction of 1960’s England filled the screen. We were giddy. I was a huge Who fan, and after Quadrophenia ended, The Kids Are Alright was more icing on the cake. Our prior bong hits had retained their potency, and the theater was heavy with pot smoke. As we all watched Townshend rough up his guitar, the kids in the theater became one with the screen, and with each other. Our collective heads were rhythmically nodding along as Baba O’Riley hit its groove, and as Daltrey belted out “Teenage wasteland, oh yeah, it’s only teenage wasteland…”, you could feel the excitement building as the song reached its crescendo. And then, as though it had been choreographed on Broadway, a sea of fists rose toward the ceiling, and a thousand voices shouted in unison, “They’re all wasted!!” It was a transcendental moment. We burst out from the dark theater, and were instantly blinded by the yellow morning sunlight. As the rest of the world was waking up and going to work, we staggered back to Neil’s apartment, physically and emotionally drained. To this day, I regard that evening as the singularly most memorable night of my youth.

1979 was fantastic. Neil still had his spiffy little blue Pontiac Sunbird, and driving with Neil was an escapade. Together, we foreshadowed Wayne and Garth by decades. Neil’s Sunbird was hipper than Garth’s Pacer, but only slightly. Neil was a maniacal driver, unfazed by Manhattan traffic. Parking didn’t bother him. He had a knack for finding curbside parking, and maneuvering his car into the tightest little spaces. Parking tickets, a common occurrence, were paid by daddy. His building had a garage below, so finding parking upon returning back home was never an issue. The Sunbird mostly functioned as a four-wheeled jukebox. I remember one afternoon, we pulled into a parking spot on the street outside a pizzeria, the car stereo blasting XTC’s “Life Begins at the Hop”. We loved XTC, and both of us were groovin’ to the beat. As he turned off the engine, the song took on new life, undistorted by engine noise. We were hungry, but neither of us made a move to exit the car. We just sat there, mesmerized by the music as it totally enveloped the car’s interior. Why this particular moment stands out is hard to say. I think it was a confluence of things: beautiful summer weather, a great sound system, an excellent song by a favorite band. We were young, we were best friends, we had few worries, no agenda, and were living in New York City. All the goodness of life fused together in one moment, in that unassuming little Pontiac Sunbird.

The rest of the year was amazing. We saw The Clash at the Palladium in September, on Yom Kippur no less. Neil’s mother was livid. “I’ll atone two days in a row next year”, he told her, “but I can’t miss this show.” The first opening act was Sam & Dave, who were riding a resurgence thanks to The Blues Brothers, who took their cover of Soul Man to number one. The second act was The Undertones. The Clash then came out and tore the house down. The iconic image of bassist Paul Simenon brutalizing his bass on the cover of the album London Calling was taken at that show. Three months later, I was back in town for Christmas, and on New Year’s Eve we rang in the 1980’s at the Palladium again, this time with The Ramones.

The fun continued in the early ‘80’s, although nothing could really top the intoxicating days of 1977, ’78, and ’79, when punk was really taking hold in NYC. Even though Neil and I drifted apart somewhat, there was still that buzz of anticipation when we made plans to do something. I didn’t have anything scheduled for New Year’s Eve, 1980. I called Neil, who told me he was going out to a club with Elizabeth, a girl he had started dating. He pleaded with me to come along, mainly because we hadn’t seen each other since the summer, and partly because he wanted me there as a buffer. He didn’t want to spend the night with Elizabeth as his only company. Neil was always a zero-drama guy, so this struck me as odd. I arrived at Neil’s apartment around 10 p.m. He opened the door, and I was shocked by how thin he’d become. He’d always been pudgy. Now he was positively gaunt. I commented on it as I entered the apartment, but he brushed it off. “Sometimes I forget to eat”, he said, laughing. He introduced me to Elizabeth, who was sitting on the couch. She was about five-foot-six, curly brown hair, dark eyes, and a great smile. A knockout. I was impressed. She greeted me, and I heard the British accent. Cool, I thought, he’s hooked up with a fellow Brit. There were a few bottles of booze on the coffee table, a fridge full of mixers, and of course, the ever-present bong. In short order, we were majorly wasted, and soon out the door.

We were heading to a dance club called Berlin on West 21st and 5th, which was not too far from Neil’s apartment. I thought we would just walk there; it was only 12 blocks away. We hit the street, and Elizabeth immediately hailed a cab. “We have to make a quick stop uptown”, Neil said. Fine with me, I thought. Whatever. I was nicely buzzed in the cab and wasn’t paying much attention to where we were going. After a few minutes I looked out the window and saw that we were way uptown, in a part of the city that Lou Reed immortalized in I’m Waiting for the Man. We pulled up in front of a Harlem tenement in serious disrepair, and Elizabeth dashed out and rang a doorbell while we waited in the cab. She was quickly buzzed upstairs and disappeared. I asked Neil what was going on. He said she was getting some “supplies” for the evening. Neil and I had smoked pot many times. We had a fondness for nitrous oxide, and we had done some ecstasy a year before at a New Year’s party at the Grand Hyatt, hosted by a college friend of mine (who synthesized the ecstasy himself in a laboratory). Other than that, we mostly drank, so this sojourn for drugs was out of character, and undeniably creepy. I asked him what exactly Elizabeth was getting. “Um, heroin”, he said, nonchalantly. “What?!”, I cried. I was stunned. He explained that Elizabeth was using it when he met her, and she convinced him into try it as well. The previous summer, Neil had mentioned that some of his acquaintances in England had started doing it, and that he thought it was an idiotic thing to do. He mentioned how one of his friends, a guy named Adam, I think, had completely ruined his life, couch surfing until he was eventually was beat up and kicked out of a cousin’s place for stealing and selling his belongings. I was upset, and Neil knew it. I asked if Elizabeth had brought this trend over with her from England.

“She’s not actually from England”, Neil said. “She’s from New Jersey.”

“New Jersey?” I said. “What about the accent?!”

“It’s fake”, he said, sheepishly.

I knew Neil was terrified of needles, so I couldn’t imagine him injecting heroin into his body, or having anyone else do it for him. He told me he snorted it. I tried to convince myself that maybe snorting it wasn’t too terrible, kinda like cocaine, but to no avail. I was perturbed. Elizabeth quickly returned, and Neil and Elizabeth discreetly snorted the stuff in the back of the cab, as we headed back downtown.

The dynamic between Neil and Elizabeth was crystal clear. She dangled drugs like a worm on a hook, and with Neil’s addictive personality, he took the bait every time. She convinced herself that his interest in her was a sign of affection. It was distressing and dysfunctional and disturbed me greatly.

The cab let us out at the club door. I don’t know whether it was our altered state, my troubled mindset, or if the club was truly as skanky as it appeared, but there was a menacing atmosphere that blanketed everything. The music was more industrial-type punk, and it was deafening. The lights were pulsating out of sync. It felt like Edvard Munch’s “The Scream” had suddenly come to life. The three of us retreated to the cushioned bench seating that bordered the dance floor. We wedged ourselves between a few emaciated revelers. The volume made conversation nearly impossible. Elizabeth shouted that she was going to get some drinks. She got up, and immediately someone took her seat. Neil shifted over, and we were lodged next to each other. We stared at a few people dancing erratically. I leaned in close to Neil.

“I’m a little worried about you”, I said.

“I know”, he said.

“Should I be?”, I asked.

“Yeah, probably”, he said, glumly.

“You’re into this more than I realize, huh?” I asked.

“Yeah”, he sighed, looking away.

“So what do we do about it?”, I asked.

“I really don’t know”, he said quietly.

Elizabeth returned with the drinks. I can’t recall the rest of the evening.

I went back to Binghamton and finished out my final year. Unfortunately, in the early ‘80’s, James Herriot’s veterinary books were at the peak of their popularity, and everyone assumed that being a veterinarian meant examining cute little calves in Mrs. Johnson’s quaint barn and getting paid in homemade apple pies. Applications to veterinary schools soared and the admissions competition was brutal. Despite my excellent grades, my application was rejected by Cornell University’s College of Veterinary Medicine. My other friends had all gotten into grad school. My then-girlfriend broke up with me. Dejected and with no immediate prospects, I needed to get far away from New York. I applied to a Master’s program at the University of Florida. The master’s degree would enhance my qualifications for veterinary school (I wasn’t about to give up), and the University of Florida had an excellent veterinary program.

If the distance from NYC made Binghamton another country, then Gainesville, Florida was another planet. From 1981 to 1983, I rarely made it back to NYC, and Neil and I barely kept in contact. Around that time, Neil and his family moved back to London.

After completing my Master’s degree in immunology, I again applied, and was finally accepted, to the University of Florida’s College of Veterinary Medicine, class of 1988. The agonizing battle was over, and the elusive Doctor of Veterinary Medicine degree was finally in my sights. On the first day of veterinary school, I met a classmate with whom I had an instant chemistry, and we became inseparable. Two years later, we were engaged. My contact with Neil had consisted of semi-annual airmail letters. I received his letters, with that distinctive blue “par avion” stamp on it, with elation. His letters were rambling and hilarious, but rarely discussed anything serious. After that night at Berlin, we never mentioned drugs again. We kept things light.

The wedding was set for the following May. I sent Neil an invitation. I expected the odds of Neil traveling from London to Lake Ronkonkoma, Long Island, were very slim, but to my utter shock, he said yes. Not surprisingly, he arrived late to the wedding and I barely had a chance to speak with him, let alone spend any meaningful time with him. He was lively and cheerful, greeting the friends who had met him previously, dancing with several women, and charming everyone he encountered. I tried to convince myself that perhaps he had cleaned up his act, but in my heart, I knew otherwise.

I graduated veterinary school in 1988. Barely a year into our marriage, things were already a little rocky, and the wife and I briefly separated. Jobs were scarce, and I knew I wanted to come back to the Northeast. I joined an uninspiring veterinary practice in Plainville, Connecticut, a city that lives up to its name. I dashed back into Manhattan every chance I got, but that only worsened the dread of returning. The wife got a job in nearby Oxford, Connecticut, and after a few months apart, we reconciled. Both of us were disillusioned with private practice, though. We both applied for internships, not knowing what would happen if we both got accepted at different schools. In the end, I was accepted to the University of Pennsylvania. She got rejected from all of the programs to which she had applied. This would become a recurring theme in our marriage. We packed up our belongings and headed to Philly.

The year spent in Philly was a rough one. I loved my fellow interns, and I received a great education, but west Philadelphia was a war zone. The daily goal was to get from your apartment to the veterinary school and back without being mugged, beaten, or stabbed. Most days, I succeeded. One evening, I was held up at gunpoint. Our car was set on fire. It was treacherous.

One afternoon, I received a phone call from Neil. He was back in New York for a few days and wondered if we could somehow meet up. I hadn’t seen him since the wedding. I told him that I was currently on my ER rotation and couldn’t get away to New York. He said that Philly was a short Amtrak ride away, and asked about stopping by the vet school and saying hi. I was excited at the thought of seeing him and said yes. A few days later, he arrived at the train station and grabbed a cab to veterinary school. I was paged to the lobby, where I met him. He was impressed to see me in scrubs with a stethoscope around my neck. I gave him a tour of the emergency room, where he found the sights and smells unbearable. He fled back into the waiting area, where there were two empty seats where we could sit and chat. “So, I guess now you’re Doctor Wanker instead of just plain wanker”, said Neil, smiling. He was clean-shaven and less pale than normal, but was still pretty thin. I asked how his life was going, and he said that things were on the upswing. His father had given him money to open a record shop in London. The store was barely turning a profit, but he loved owning it and working there. He combined all of his own records into the store’s inventory, and he said he felt like the shop was his personal, massive record collection. He finally had the perfect job. I was trying to figure out a way to tactfully ask about his past habit. Thankfully, he relieved me of the task. “I enrolled in Narcotics Anonymous”, he said, and told me that he was attending their meetings regularly. At one of the meetings, he met a wonderful girl named Jocelyn and that they had fallen in love and were getting married! He proudly stated that he was completely drug free. “Oh, you’re not going to believe this,” he said. “I’m at my first meeting, and a guy who looks vaguely familiar enters the room, peruses the crowd, and then goes up to each member and introduces himself personally to everyone. He comes to me, extends his hand, and says, ‘Hi, I’m Elton.’” “No fuckin’ way!” I said. “Yes fucking way”, he said, in mocking British Brooklynese. I asked if he conversed with him. He said, “I asked if I could borrow a pound for the vending machine!” We laughed. I told him I couldn’t wait to meet Jocelyn. “I have to see, in the flesh, the only woman on Earth who could possibly put up with you.” We smiled. “Anything else going on?” I asked. “Um, yeah there is”, he said. There was a long pause. “The thing is,” he said, lowering his head, “during the time I was using drugs in New York, I managed to pick up that virus you’ve been hearing about. I’m HIV positive.” I could feel the blood drain from my face. In 1990, a diagnosis of HIV was a death sentence. “What?!”, I said in disbelief. “It’s okay”, he said. “I’m doing all right at the moment.” I grew silent, groping for words. “I’ll be fine, really”, he said again. I asked if he was taking any medication. He said that he was, but that “sometimes the treatment is nearly worse than the disease.” He said he would be going back to England in a few days, to run his record shop and be with Jocelyn. As I escorted Neil to the lobby, we promised to keep in touch better. We hugged goodbye.

My internship quickly wrapped up, and the wife and I moved to Baltimore where I began working at a feline-only veterinary hospital in Towson. We bought an adorable little house, and this time, Neil and I actually did keep in touch, writing each other every few months. In 1992, he wrote that he was coming to the U.S. to visit some friends of Jocelyn’s, and asked if it would be okay if they came and visited us in Maryland. Of course I said okay. Our house was small, but it had a guest bedroom, a sizeable backyard, and a deck with a built-in hot tub. I wanted to show him my fancy new digs and get to meet his wife and spend some quality time with him. When he finally arrived, he looked great. He was thin, but clearly content. He still had his biting wit, but he had definitely mellowed. Jocelyn was wonderful and kind. She was incredulous that Neil had “normal” friends. “All of his friends so far have been either idiots or derelicts”, she said. We spent a truly congenial three days together, strolling around Fells Point and Baltimore’s inner harbor. I took Neil and Jocelyn to a well-known barbecue restaurant in downtown Baltimore. Neil scanned the menu, and in classic sarcastic fashion, sneered, “leave it to the Americans to come up with items like ‘pulled pork’ and ‘pit beef’.” I said, “Well, maybe we can have some mouth-watering ‘digestive biscuits’ and ‘blood pudding’ for dessert”. Neil smirked. Jocelyn grinned. “Touché”, she said, poking Neil in the ribs.

Life in Baltimore was pleasant enough, but predictably, my love-hate relationship with private practice was drifting toward the hate side, and I found myself craving the mental stimulation and cutting-edge excitement of academia once more. My wife was in the same boat, and again we found ourselves at a crossroads. We both applied for residency programs at multiple veterinary schools across the country, each agreeing to follow the other to wherever one of us got accepted, and not sure exactly what to do if both of us were accepted to different schools. We both wanted to stay on the East coast, however, the competition for these residencies was brutal. Over her protestations, I applied to Colorado State University as a safety net; one of my professors from University of Florida had clout at CSU and he promised to write an excellent recommendation needed. Neither of us got accepted to any of the east coast veterinary schools. I was accepted to CSU. Déjà vu. We sold our house, packed our belongings, and warily headed west to Fort Collins.

My small animal internal medicine residency was a three-year combined residency/master’s degree program. The plan was for me to do my residency while my wife worked at a private practice. Frustratingly, veterinary jobs were scarce in Fort Collins, and my wife couldn’t find veterinary work. She was distraught. After a miserable, tension-filled year, she announced that she was going back to Maryland where she would easily find work. I was to join her after my program. I explained the circumstances to my unsympathetic residency advisor and petitioned them to let me shorten the program from three years to two. They reluctantly agreed. She packed up half of our stuff and drove back to Maryland. I rented a small one-bedroom apartment by myself, and finished out my residency. The program was intensive and seldom did I have any weekends where I wasn’t required to be at the university for early morning rounds. When I did have the rare weekend free, I stealthily drove an hour into Denver and visited some bars and clubs that I had heard about. Alone and relatively anonymous, I was free to dip my toe into waters that, until now, I had only dreamt of swimming in.

My residency ended in May of 1995. I rented a van, packed my stuff, and drove across the country back to Maryland, to the house in Kensington that my wife had rented upon returning from Fort Collins. I had accepted a job as the chief of staff at a national corporate veterinary practice in Columbia, Maryland, not far our new home. I was happy to be back in the Eastern half of the country. I’ve always been a city boy, and Washington DC was new, exciting turf. When we weren’t working, my wife and I would explore DC, visiting famous landmarks, trying new restaurants, shopping in hip, funky stores, and generally pretending that our marriage was salvageable.

One evening I came home from work, and my wife informed me of a message on the answering machine, from Neil’s sister. I had met Neil’s sister once, very briefly, during that Labor Day weekend I visited him in Great Neck. We had no relationship, so it was beyond unusual for her to call me. She gave no reason for the call, but left a phone number where I could reach her. I had lost touch with Neil during my days in Colorado, and although I hadn’t re-established contact since returning east, I assumed that he and Jocelyn were living in marital bliss in London. Mindful of the time difference, I waited until morning before calling Neil’s sister back. It was a sleepless night.

The next morning, Neil’s sister informed me that Neil was very sick in a hospital in London. She gave me the phone number of a direct line to Neil’s hospital room.

I called and Jocelyn picked up. I could hear monitors pinging in the background. I asked Jocelyn if Neil was okay. She told me that Neil was very sick. She said that he had been battling a host of symptoms for months, and finally four months ago, he told her that he was resigned to his fate and he simply couldn’t fight anymore. His condition rapidly worsened, and now “we’re at the end”. I asked if I could talk with him, and she said that he was too ill to speak, but she would put the phone by his ear. “Okay”, she said, “he’s listening. Go ahead.” My brain flooded with countless memories of the years we hung out together, and in a trembling voice, I spewed out one hilarious incident after another, one memorable event after the next. A barrage of fond recollections poured out of me, until I was breathless. I then said goodbye. Jocelyn picked up the phone. “My god!” she said, incredulously. “I don’t know what you just said to him”, she continued, “but he hasn’t smiled like that in ages.” Retaining my composure as best as I could, I said goodbye to Jocelyn. I don’t know how gently Neil went into that good night, only that he did, and that a major chunk of my life went with him.

In Kensington, life marched on, but not smoothly. As expected, my marriage dissolved. I wish I could say it ended honestly and courageously. It didn’t. Instead of coming out of the closet, I waited until the entire house collapsed around me. I separated from the wife and moved to nearby Baltimore. I could finally be true to myself and live my life as a single, out gay man. I was a quick study.

One evening, while leafing through The Advocate in my Baltimore bachelor pad, I spied an article about the upcoming Gay Games. This is a cultural and sporting event specifically for the LGBT crowd. The Gay Olympics, essentially. That year, it was to be held in Amsterdam. Emboldened by my new freedom and feeling kinda adventurous, I decided to attend, traveling solo. I booked a flight, reserved my hotel, and bought an Amsterdam travel guide. On arrival, I was amazed at how beautiful, laid back, and friendly the city was. The streets were teeming with affable gay athletes and gracious gay tourists. I had a list of scheduled events and street parties, and I made friends quickly. I had little interest in attending the sporting events. Instead, I explored the museums and monuments, strolled the picturesque streets, and chilled out at canal-side cafes, eating lunch while watching tour boats drift by.

I read in the official Games guide that the AIDS Memorial Quilt was to be displayed for these Games. The Quilt, a memorial for people who have died of AIDS, is comprised of individual quilted panels, sewn together by the friends, lovers, and families of the deceased. The Quilt has grown so vast that it is almost impossible to display in its entirety. Fortunately, a significant portion of it was being exhibited in beautiful Vondelpark, an outdoor park akin to our Central Park. I made my way to Vondelpark and there, unveiled on the lush green lawn, was panel after quilted panel of personal tributes to those who were taken by AIDS. The mood was solemn as visitors strolled the paths between each large section of quilt. My gaze alternated between the panels in front of me, and the vast stretches of panels that radiated in the distance. I was soon overwhelmed with the enormity of the cumulative loss that the quilt embodied. I was impressed by how well each small panel effectively captured the warmth and humanity of the person it represented, and I began to feel Neil’s presence in every one of those small quilted panels. When I spotted a photo, sewn into a panel, of a young man with a passing resemblance to Neil, I felt weak. Benches were scattered throughout the park, and I found a secluded one nearby. Like many others that afternoon who were mourning the loss of those who were close, I silently wept as I reflected on the friend I missed so terribly.

The Games ended, and I bid Amsterdam a tearful adieu. I returned to Charm City invigorated. Baltimore’s gay scene was small, but I was making the most of it, spending the weekends dancing and carousing. During my second year in Baltimore, after many dates that ultimately went nowhere, I entered into a nice relationship and was soon falling in love with a handsome young PhD student at Johns Hopkins.

In the spring of 1998 I received a letter from a headhunting agency based in New York. The ASPCA was looking for someone to fill the lofty position of Vice President of Animal Health, and incredibly, they were interested in me! Though I was carving out a life for myself in Baltimore, I knew I would never be a Baltimorean at heart (my obsession with John Waters notwithstanding). I’m a New Yorker. My quest to become a veterinarian had led me all over the country, from Binghamton to Florida to Connecticut to Philadelphia to Baltimore to Colorado to Kensington to Baltimore again. I’d been away from New York City for almost 20 years! I tried planting roots in some of these places, but they never took hold. It was time to come back home. I interviewed at The ASPCA, and they hired me. The boyfriend and I agreed to try the long-distance romance thing. I prepared for my triumphant return to New York City.

The rental agent from Citi Habitats showed me many apartments. I chose a funky, spacious studio apartment in the Village, at Bleecker and Broadway. I returned to Baltimore, rented a U-Haul and packed up again. Destination: NYC. Home.

A few months after Neil died, it was discovered that a new class of AIDS drugs called protease-inhibitors, in combination with other antiviral drugs — the so-called AIDS cocktails — were a powerfully effective treatment for AIDS. People on the brink of death were brought back to life, like the Phoenix from the ashes. I became consumed with the thought that if only he could have held on for a few more months, things might have been very different. The sorrow and regret were too much to bear. For months, I coped by not thinking about him at all. Now, with my return to the city, I feared that I’d be bombarded by constant reminders of those youthful days.

Unexpectedly, it never happened. Resurrecting past memories by returning to the scene of the crime doesn’t work in New York, because the crime scenes will likely have disappeared. Our favorite haunts — the 8th Street Playhouse, The Bleecker Street Cinema, The Bottom Line — all vanished. The Palladium became a NYU dormitory. CBGB is a Jon Varvatos Store. The Café Figaro, gone. Sigh. Even encountering the places that managed to stave off extinction failed to revive any memories. I walked past the McDonalds where Richard Hell asked Neil and me for a light, and it now seems unfathomable that it really happened there. The Washington Square Park where we smoked weed and watched hippies frolic in the fountain seems to have been in a parallel universe. I found myself walking past Neil’s old building, the Brevoort East. I stopped in front and stared, and honestly, I could barely recognize the building. It’s not easy to reminisce here. In New York City, the present is always so strong that the past gets obliterated. It’s a great city for making memories, but a difficult one for resurrecting them. I’m fine with that. Cities are like people. They grow. They change. They evolve. To carve out a life for myself in NYC, I’d have to grow and evolve along with it. Otherwise, I’d end up feeling like a tourist in my own city, and that gets really tiresome.

Fortunately, upon my return, I had no problem adapting to the post-Neil version of New York City. I went through a second teen age, partying and clubbing with a new crowd of friends. Twenty years earlier, it was The Ritz, Danceteria, CBGB, and Irving Plaza. Now it was The Roxy, Twilo, Limelight, and Sound Factory. My focus was different in the ‘90’s. I was trying to be the best veterinarian I could be, while evolving as a gay man in the world’s most gay-accommodating city.

The tribal house music in the gay clubs was very different. I hated it. I still was a punk at heart, and luckily, New York was still the epicenter. My live music fix remained easily attainable. At every Patti Smith concert (and there were many), as her band was crankin’ that last verse of Gloria, I’d imagine Neil standing next to me, equally digging the sonic assault. Then the song would end, and he would be gone.

These days, I look in the mirror and see a guy in his 50’s staring back. I’m not sure how the fuck that happened. The concerts are fewer, and my clubbing days are over. Weed and Ecstasy have given way to Lipitor and Plavix. I own my own veterinary hospital, and I’ve been in a relationship that’s going on its fifteenth year. Life is calm. Life is good. When I’m feeling nostalgic, and thoughts of Neil pop into my head, I don’t dwell on what might have been. Enough time has passed. Now I whip out the iPhone, pop in the ear buds, and crank up his favorite song, Transmission by Joy Division. The stark opening bass notes begin, and in seconds I’m back in Neil’s apartment, laughing, as he grabs a broom and feebly attempts to play air bass. It was always the music that bonded us together, he and I.

It still is.