Feline Body Parts – The Kidneys of a Cat

Body Parts – The Kidneys

by Arnold Plotnick, MS, DVM, ACVIM

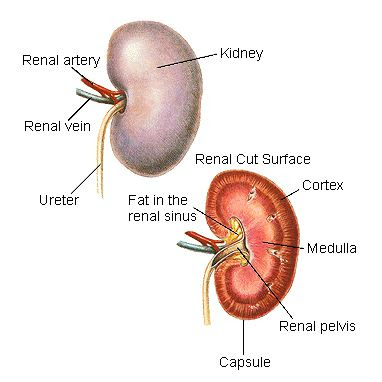

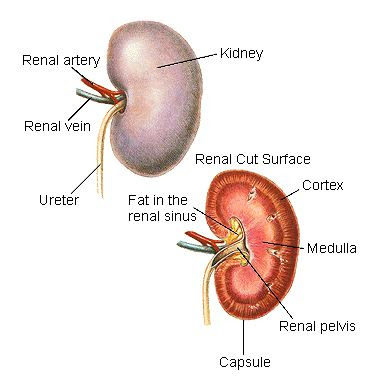

Like all mammals, cats have two kidneys, one on the left, and one on the right. They are shaped like…kidney beans, of course. Blood flows into the kidney through the renal artery, and leaves via the renal vein. As blood passes through the kidney, toxins are filtered from the bloodstream. These toxins go into the urine, where they are excreted from the body. The kidney also produces hormones. One of these hormones, called erythropoietin, is responsible for the production of red blood cells from the bone marrow. Other hormones produced by the kidneys help regulate blood pressure.

As most cats age, kidney function gradually declines. Eventually a point is reached where the kidneys can no longer maintain their normal function, and the toxins in the bloodstream accumulate. This condition used to be called chronic renal failure, but these days, veterinarians prefer the term chronic kidney disease (CKD). Unless the underlying cause can be discovered and treated, CKD invariably progresses. In most cases, an underlying cause cannot be found. Why most cats eventually develop CKD remains one of veterinary medicine’s biggest (and most frustrating) mysteries.

The primary clinical signs of CKD in cats are excessive thirst (polydipsia) and urination (polyuria), decreased appetite (anorexia), weight loss, and occasional vomiting. Because these signs are also often seen in other illnesses, several tests are required to confirm a diagnosis of CKD. These include a complete blood count, serum chemistry panel, and urinalysis. The finding of dilute urine, coupled with an elevated level of kidney toxins in the blood, indicates that kidney function is compromised. The two primary renal toxins that we monitor are “blood urea nitrogen” (often abbreviated BUN) and creatinine. Other abnormalities, such as elevated phosphorus, low potassium, and anemia (decreased amount of red blood cells) may also be detected. Although CKD is incurable, a variety of diet and drug interventions are now available that may slow the progression of the disorder, improve the cat’s quality of life, and extend a cat’s survival time. Cats who are suitable candidates may be eligible for a kidney transplant. This is a major endeavor requiring the expertise of a skilled surgical team at a university or referral center. The procedure, as you might expect, is very expensive, and post-operatively, the cat will require long-term administration of drugs to prevent rejection of the transplanted kidney.

Although chronic kidney disease is by far the most commonly seen feline kidney disorder, other kidney ailments are occasionally encountered in cats. Acute renal failure (the currently preferred term is acute kidney injury, abbreviated AKI) is a disorder characterized by a sudden, dramatic decrease in kidney function. This is a serious condition that, if not recognized and addressed quickly, can lead to rapid decline and possible death. Unfortunately, the clinical signs of AKI – poor appetite, vomiting, extreme lethargy, weakness, decreased urine production – are nonspecific and may result in delayed recognition that the cat is ill. The most common causes of AKI in cats are ingestion of ethylene glycol (antifreeze) and ingestion of lilies. Many people are unaware that all parts of the lily plant – even the pollen – are toxic to cats if ingested. Other possible causes include unintentional administration of toxic drugs (for example, giving ibuprofen to a cat), and any situation that results in decreased blood flow to the kidneys (for example, anesthesia).

Bacterial infection of the kidney, called pyelonephritis, is occasionally seen in cats. In this disorder, one or both kidneys become enlarged and tender, and the cat usually develops a fever, high white blood cell count, and poor appetite. Elevated BUN and creatinine levels may occur if kidney function becomes impaired. Pyelonephritis usually requires hospitalization and treatment with intravenous fluids and antibiotics.

Kidney stones (nephrolithiasis) are uncommon in cats and are usually of minimal clinical consequence. However, if a small stone leaves the kidney and becomes lodged in the ureter (the tube that connects the kidney to the bladder), the obstruction of urine flow causes a pressure buildup in the kidney that can lead to functional impairment and, if not relieved, ultimate destruction of the kidney. Fortunately, this is an uncommon occurrence.

Feline infectious peritonitis (FIP) is a viral infection that may affect cats of all ages, although it has a predilection for young cats. There are two forms of the infection, the “wet” form, in which fluid accumulates in the abdomen (and sometimes the chest cavity), and the “dry” form, in which clusters of inflammatory cells infiltrate various solid organs in the body. The liver and kidney are the favorite target organs for the FIP virus. When FIP affects the kidneys, their function eventually becomes impaired as the viral infection progresses. At present, there is no treatment for FIP, and all cats eventually succumb to this disease. Treatment of FIP, however, is a very active area of research, and veterinarians are more optimistic than ever that an effective treatment will soon be discovered.

Sadly, cancer of the kidney is a well-documented illness in cats. The cancer can be primary, i.e. arising from the kidney itself. An example would be a renal carcinoma. In primary kidney cancer, usually only one kidney is affected. Cancer can also spread from other organs to the kidneys. The most common type of cancer occurring in feline kidneys is lymphoma, in which both kidneys are infiltrated with cancerous lymphocytes. Renal carcinomas, being unilateral, may be amenable to surgical removal. Lymphoma of the kidneys, however, is almost always bilateral, and must be treated with chemotherapy.

For more on feline kidneys, check out my articles:

| “Long Term Management of Chronic Renal Failure in Cats“ |

| “New Test for Renal Disease“ |

| “High Blood Pressure“ |

| “Polycystic Kidney Disease“ |