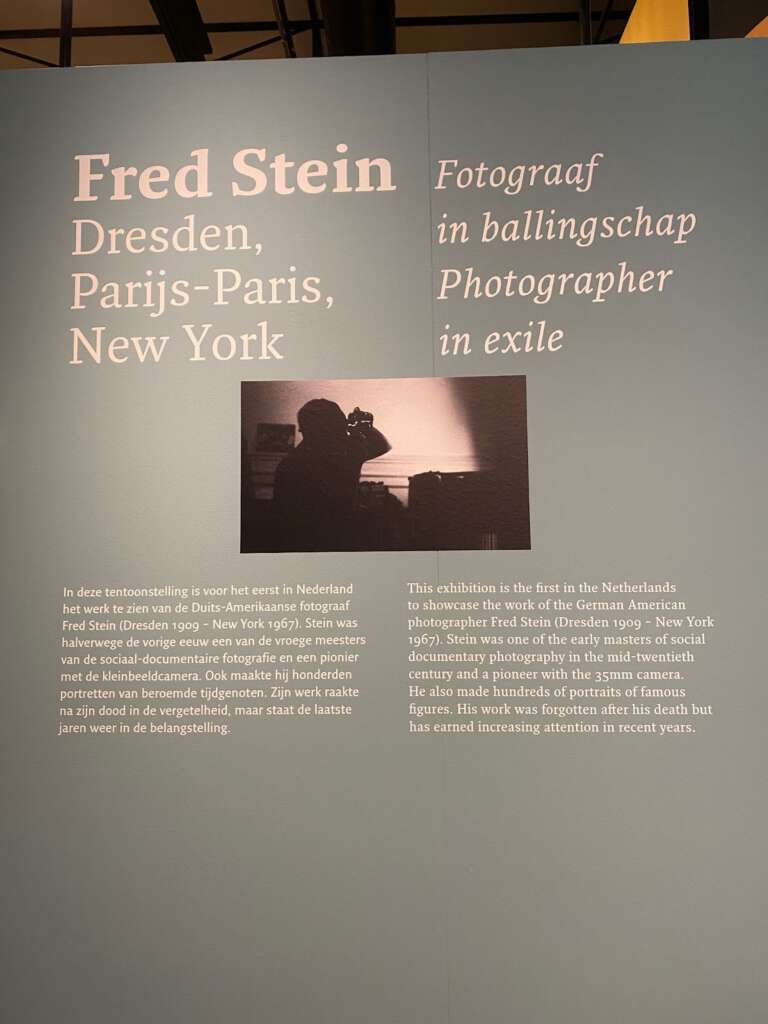

Fred Stein Photography Exhibit: Dresden, Paris, New York – at The Jewish Historical Museum, Amsterdam

Amsterdam is a great museum city, and going to the different museums is by far my favorite activity when I’m there. I like photography, and I always make it my business to stop by the two photography museums, FOAM and Huis Marseille. If I’m lucky, some of the other museums will also have a photography exhibit. Well, I got majorly lucky this time, because the Jewish Historical Museum had a fabulous exhibit about Fred Stein.

Stein was a very influential German/American photographer. He’s probably best known for his portraits, but some of his street photography was pretty amazing. His life story is pretty compelling. Stein always showed a strong activist streak. As a teenager, he became active in the Socialist Youth Movement. He was working as a lawyer in Germany, devoting most of his practice working to help the poor and disadvantaged, but had to flee his native Dresden in 1933, when the Nazis came to power. Jews were forbidden from practicing law, and his left-wing activism put him in danger of being arrested. He (along with his wife Lilo) went to Paris.

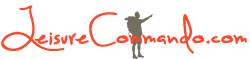

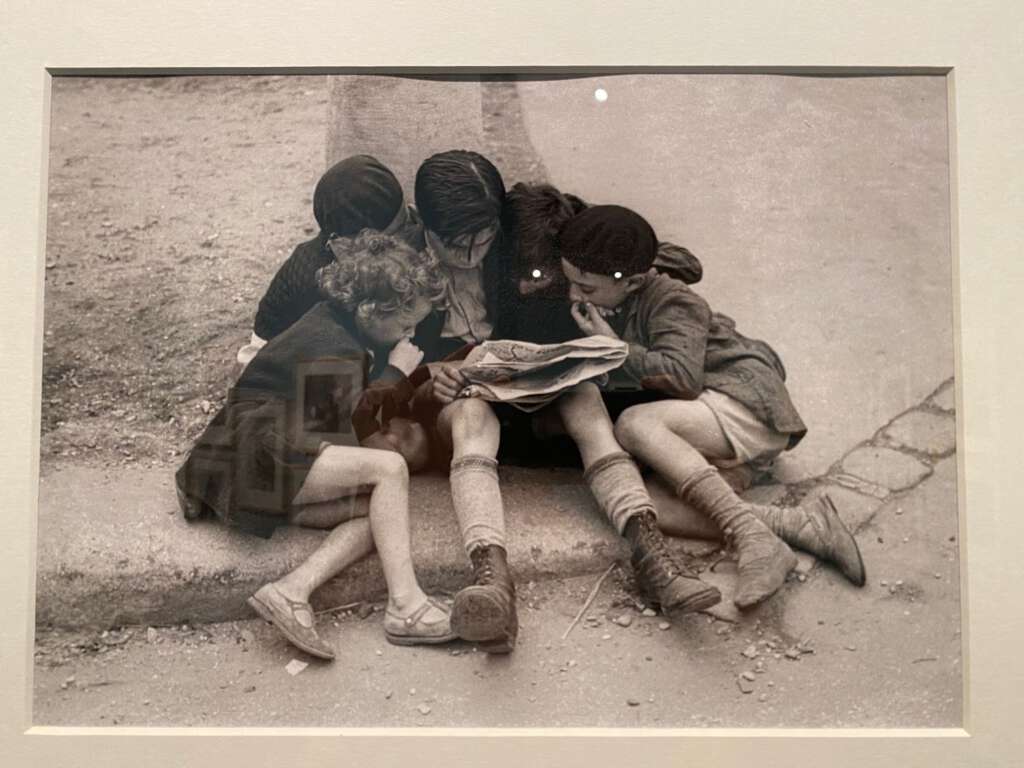

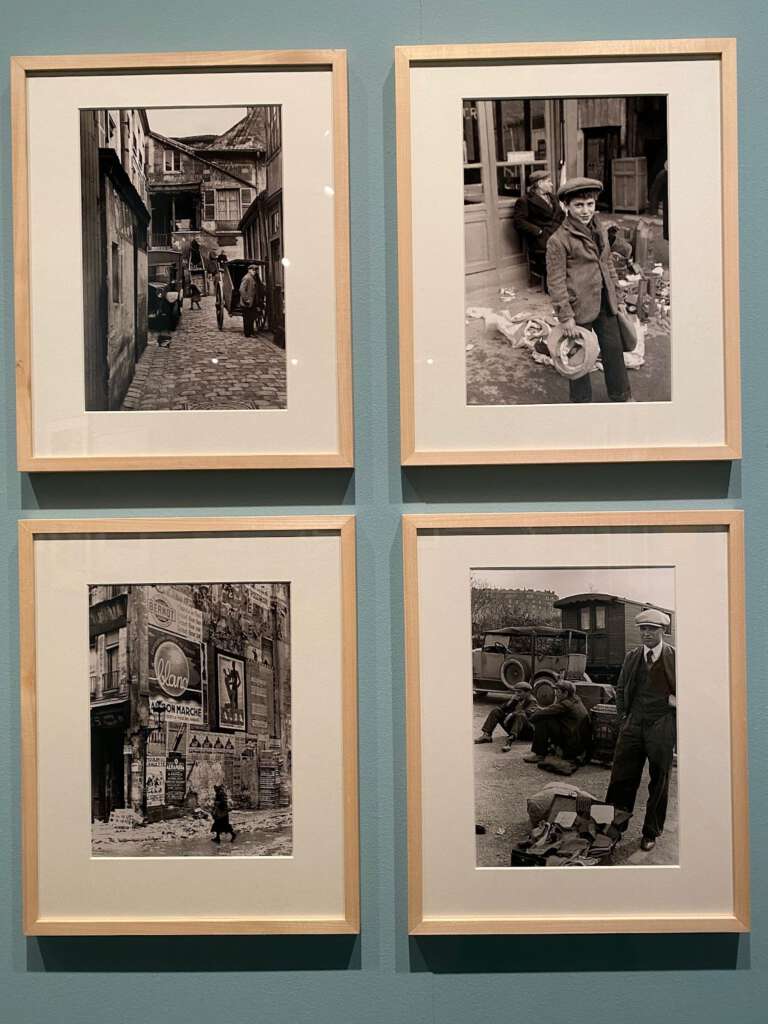

Paris was a great refuge for people fleeing the Nazis, especially for artists, writers, and intellectuals. But a lot of the people who fled Germany lived poorly because the labor market was closed to immigrants. Unable to work as a lawyer, he decided to do something very admirable: he turned his hobby, photography, into a profession. Photojournalism was an emerging field, and there were many opportunities to produce work for newspapers and magazines. In this field, there were few limitations for foreigners, and the language barrier wasn’t a major hindrance. Stein quickly mastered his Leica 35mm camera. He focused his photojournalism on topics that reflected his political and social values, documenting the poverty of the Parisian working class and the activities of the socialist movement. He also photographed everyday life on the streets. His photos became popular quickly, and within two years, he was exhibiting in Paris galleries alongside photographers like Andre Kertesz and Man Ray. The photojournalism field was competitive, but he did well, and his photos appeared in many newspapers and magazines.

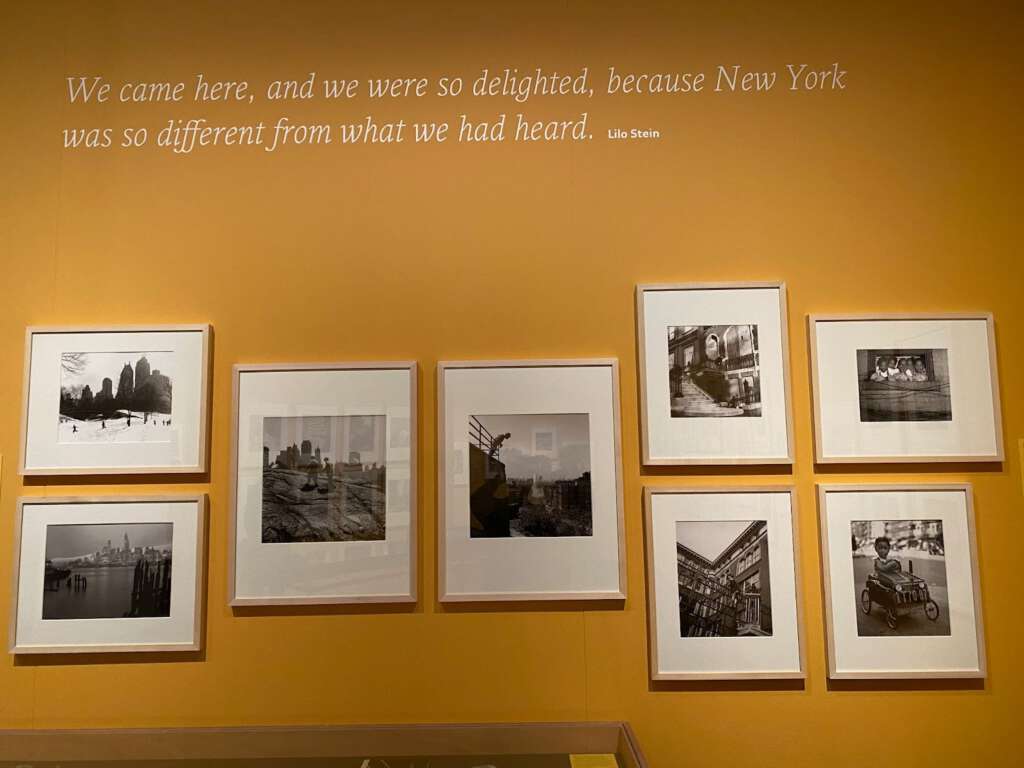

Here are a few pics from the exhibit:

After working in Paris for a few years, turmoil invaded the Stein’s lives again. Britain and France declared war on Germany. Fred, being a German, was interned in various French camps because he was considered an enemy alien. In June 1940, the Germans invaded France. Stein was released from the internment camp in Brittany. Fleeing the Nazis once again, he walked 600 kilometers to the city of Toulouse. Although Toulouse was a “free zone” that wasn’t under Nazi occupation, the Steins weren’t really safe there, as Jews and other refugees were often arrested and handed over to the Germans. With no money or identity papers, Fred and Lilo were unable to escape Toulouse. Fortunately, the American Emergency Rescue Committee in Marseille, which helped European artists and politicians to flee to the US, came to the rescue. Stein qualified for assistance due to his fame as a photographer and political activist, and he and his wife were put on a ship. They arrived in New York on June 13th, 1941. It was in New York where they went about rebuilding their lives.

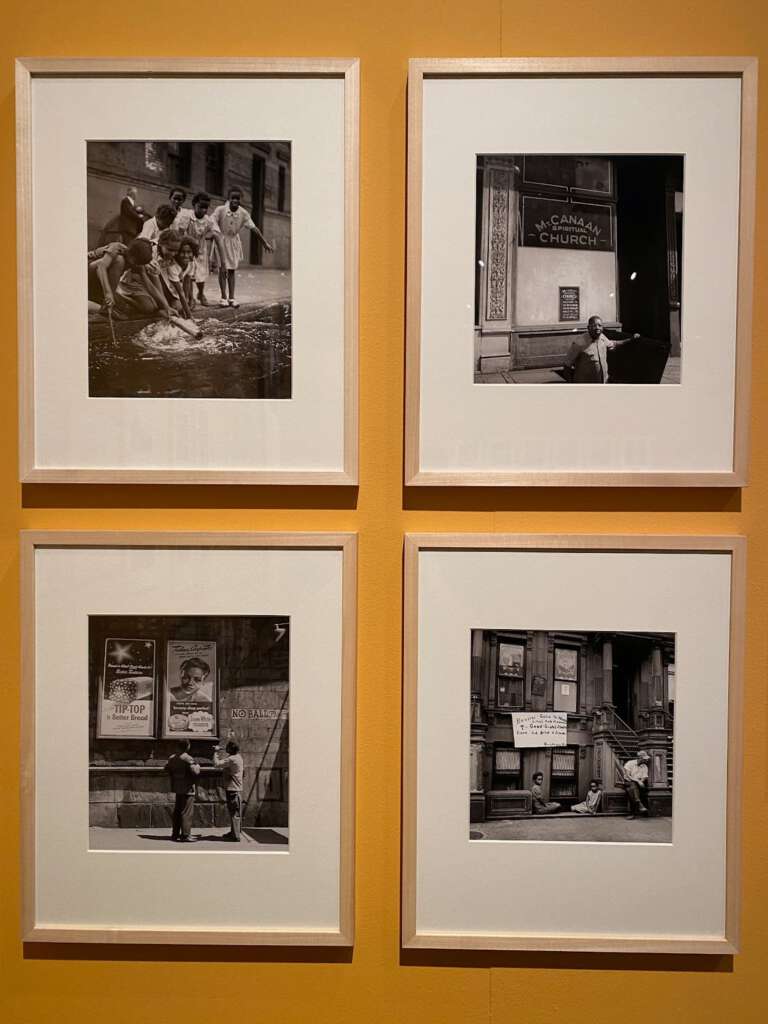

They settled down on West 145th Street in Upper Manhattan, where a lot of other German refugees settled. Fred immediately resumed his photography work, while Lilo got a job at a photo lab, which supported the family. Stein loved NYC: the noise, the architecture, the different ethnic groups, etc. He took great photos that captured New York’s diverse population in intimate moments. As an admirer of architecture, he also took a lot of photos where architecture was the main subject.

More pictures from the exhibit:

Stein did a lot of street photography in New York, initially, but when a bad hip prevented him from walking around a lot, he focused on portraits. In the early 1960’s, the West German government awarded him a very prestigious assignment: a book with a hundred portraits of prominent West Germans who played a leading role in the country’s post-war reconstruction. The book was intended to promote the image of West Germany as a new democratic state. Stein knew that some of the people sitting for him included former supporters of the Nazi regime. (West Germany hadn’t quite finished the denazification of the country after the war.) He had difficulty with this, but he made a critical reference to their dark past in his portraits of them. It was his personal way of “unmasking” them.

Stein died in 1967, at the young age of 58. His wife Lilo managed his estate until she died in 1997. After that, the couple’s son, Peter Stein, took charge of the archive. Sadly, Stein’s work fell into obscurity, and he died before photography became popular in the ‘80s and ‘90s. Fortunately, over the last two decades, Peter Stein has managed to succeed in making his father’s work more widely known.

The oppression and persecution that Stein experienced was reflected in his photography. His identity as a Jew, a left-wing political activist, a refugee, and an outsider strongly informs his work. I relate to Stein on many levels, and I really loved this exhibit.