Robert Frank’s “The Americans”

Three years ago, I made the decision to retire from clinical veterinary practice. I slowly let most of my regular clients know that I was retiring, and a few of them gave me little gifts, which was very kind of them.

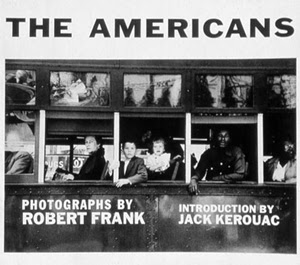

One client, Amy Cohen, gave me a book: Robert Frank’s “The Americans”, a book of black-and-white photographs. She knew that I liked to travel, and that travel photography was a burgeoning interest of mine. At home, as I flipped through the 83 photos, I wasn’t particularly moved by them. I had taken a photography course not long before that, and these photos seemed to violate many of the principles that were taught in that class. The photos weren’t artfully framed. People’s limbs were truncated, heads were cut off, and many were out of focus. I enjoyed the introduction, which was written by Jack Kerouac, but the photos didn’t leave much of an impression.

I pursued travel even more fervently in retirement. In October 2018, I joined a team of volunteers on a trip to Goa, India, to vaccinate the local dog population against rabies. All of my fellow participants took cell phone photos of their daily adventures, the best of which we shared in a WhatsApp group. One particular volunteer, Jen, took photos that were clearly a cut above the rest. They were stunning, not just in visual quality, but also in composition and technique. I was amazed that such high-caliber pictures could be taken with an iPhone, and I vowed to myself that I would learn how to do this. Back home, I took an online course devoted specifically to iPhone photography, and a subsequent one in photographic editing. My photography improved immensely, and I put these new skills to the test in December 2019, on a trip to Kenya and Ethiopia.

The following month, in January 2020, during my second Mission Rabies trip (to Ghana!), I took some of the best photos I’ve ever taken. When my fellow volunteers and I posted photos in our WhatsApp group, I was much more proud of the results.

I tried to improve my photographic skills further by watching YouTube videos created by other photographers. I’d already watched many videos about photographic technique – framing, composition, lighting, exposure, etc. I now began to gravitate more toward videos that focused on style and perception, videos that dealt more with “why” of photography, and less with “how”. As the narrators of these videos presented examples of their favorite important and influential works, a common theme emerged: photos from Robert Frank’s “The Americans” kept popping up. So, I went to my bookcase, pulled out The Americans, and gave it another look.

Amazingly, it was as if I was seeing these photos for the first time. As I slowly flipped from page to page, the mystery, the beauty, the simplicity, the intrigue of these photos hit me clearly and powerfully. I think it wasn’t until I understood the technical rules of what comprised a good photograph to fully appreciate how breaking those rules can lead to a great one. Frank’s photographs definitely broke all of the rules.

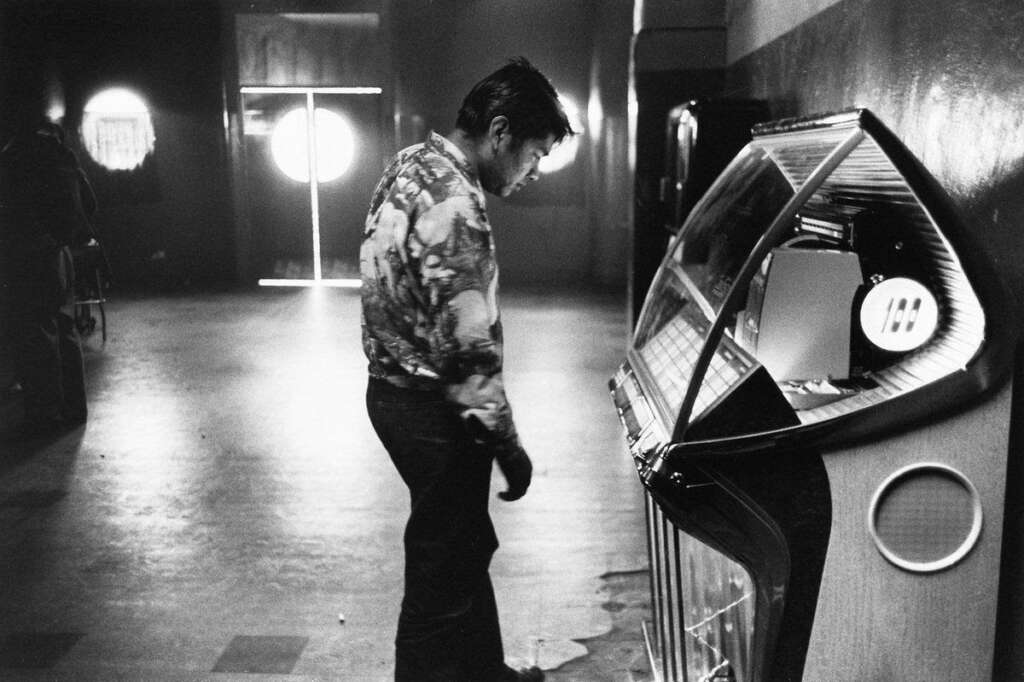

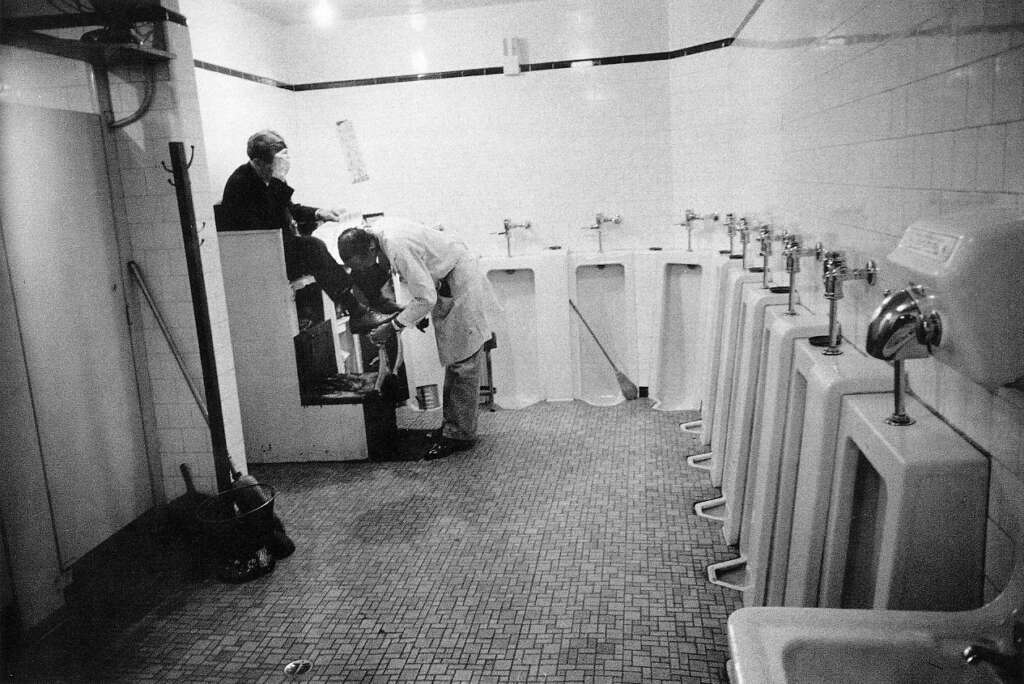

I did a little more delving into the history behind this book, and it’s fascinating. I had no idea of the immense significance of this book. In most of the articles I read, the book has been described as one of the most influential photo books of all time. Certainly, the most influential since World War II. During a time (post-war 1950s America) when the nation’s self-image conformed to what was depicted on the pages of Life Magazine, Robert Frank showed a very different America, using many of the same symbols that comprised America’s imagined identity (highways, parades, flags, cars, diners, jukeboxes), but portraying hardship and alienation, loneliness and angst. It was moody and bleak. It was hardly the stuff of the American dream.

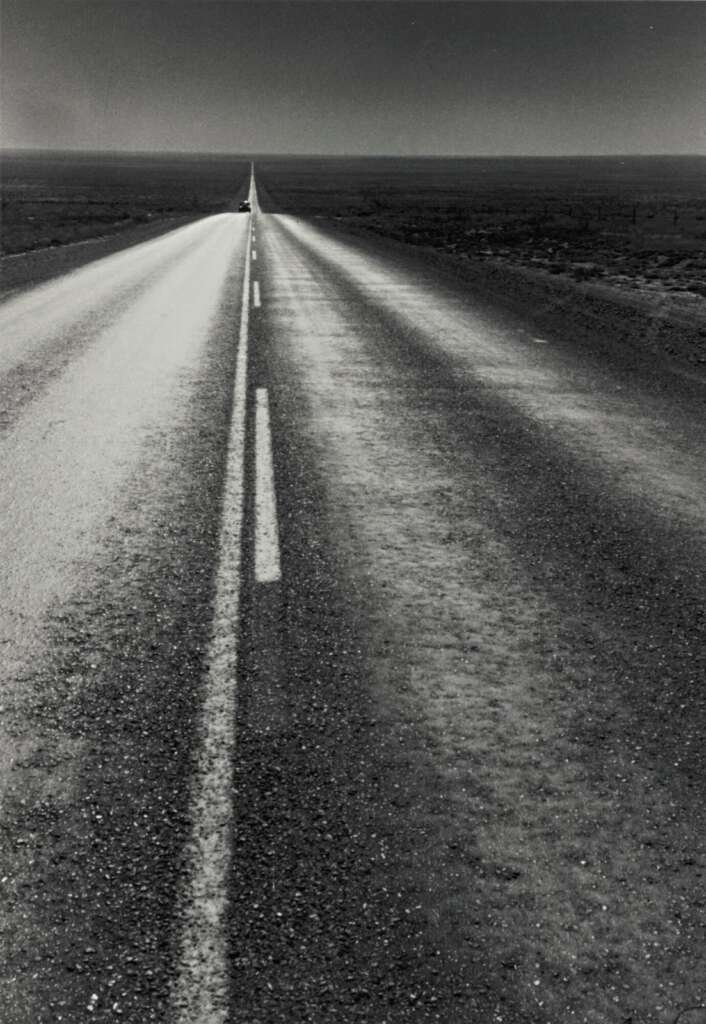

Frank was born in Zurich, Switzerland in 1924. He came to New York in 1947, earning his living as a commercial photographer. In 1954, he applied for a Guggenheim fellowship, proposing to create “an observation and record of what one naturalized American finds to see in the United States.” He bought a car, and with his wife and two children he drove across America on three separate road trips over the course of two years. Using 767 rolls of film, he took 28,000 photographs of American society at every level. The people in his photographs were ordinary Americans doing ordinary things.

Eating in diners.

Selecting a song from a jukebox.

Sitting in a car.

Getting a shoeshine.

Watching a drive-in movie.

Subjects were blurry. Horizons were crooked. Scenes were off-center. They were imperfect and grim, like the America they depicted. This chasm between the American dream and everyday life had never been depicted like this before, or since.

Frank took his 27,000 photos and edited them down to 1000. He spread them out on the floor of his studio, and then whittled them down further to a mere 83 photos. He met Jack Kerouac and showed him the photos from his road trips, and Kerouac immediately agreed to write an essay about the photos, which became the introduction to the first edition. He ordered the photos in a very specific sequence, in four distinct sections. Each section begins with a photo of an American flag, and each part has its own odd rhythm to it.

Now that racial issues have once again taken center stage in America, you certainly can’t help seeing Frank’s images of race without a heightened sensitivity and awareness. The cover photo shows one of Frank’s most celebrated and controversial images, a segregated trolley in New Orleans.

At first glance, it’s just a few passengers, some black, some white, looking out of a trolley window. But as you view it from left to right, it goes from white to black, old to young, before focusing on the face of a black man staring plaintively at the camera, inviting you to try to understand his plight. Frank did this project in the 1950s, and the south he drove through was the Jim Crow south. Being from Switzerland, he had never come into contact with the kind of racial segregation that he witnessed in America. One of his photos in the book is of a black woman holding a white baby. Regarding that photo, Frank said that he just could not fathom how a white southern woman would entrust the care of her baby to a black woman, but wouldn’t sit next to her at a lunch counter.

The first photo of the fourth section shows a man playing a tuba in a marching band, with the American flag above him. The tuba completely obscures his face.

All you see in the photo are symbols of Americana; the human element is erased, suggesting that these symbols of America are more important than the identities of the people that the symbols represent.

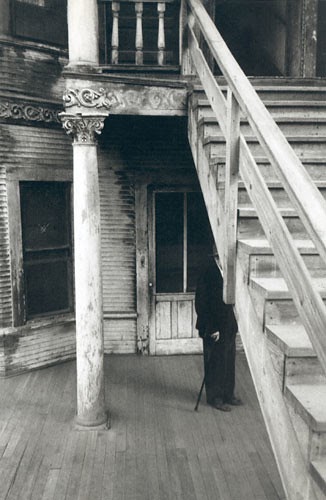

I was particularly struck by the feeling of loneliness that many of the images induce. In many of these photos, the person is isolated, cut off from the rest of the world, and you feel it strongly.

The book was initially not well received. Depicting an America that was at odds with the happy, optimistic baseball and apple-pie image of the country at the time, Frank’s photos were seen by some as derogatory, and this startled and outraged many critics. By starting each section with an American flag, it was as if he was sticking an ironic finger in the eye of his critics. Popular Photography magazine described The Americans as “a sad poem by a very sick person”. The book sold 1100 copies and quickly went out of print. Fortunately, Beat literature was popular at the time, and Kerouac’s intro did expand the audience for the book. Over time, the stature of the book has grown, and as I mentioned earlier, its influence is profound. No book has been more influential on the course of contemporary photography than this one. Before this book, photography was thought of as something that could be understood universally; anyone would look at a photo and come to the same understanding and conclusions. Frank challenged that, his images and subject matter leaving the viewer with as many questions as answers. He also challenged the idea that photos needed to be technically perfect, letting his grainy, blurry images speak for themselves.

When I look through the book, I always re-read the introduction by Kerouac. I’m a fan of his writing, and On the Road had a profound influence on my younger self, as it did for many of my generation. Kerouac’s intro is a perfect complement to the photos, and reading Kerouac’s words brings back that feeling of melancholy and wanderlust that enhances my viewing experience. The last photo in the second section of the book shows the highway, stretching endlessly into the distance, a perfect visual accompaniment to the mental image conjured up by On the Road.

My favorite form of photography is “street photography”, and The Americans is cited by many well-known, accomplished street photographers as a major influence. I can definitely see why. Street photography, where spontaneous, chance encounters with people hopefully convey some kind of raw, human element, is something I’d like to become better at.

As you can see, I’m still working on it. I’ve put Frank’s book on my nightstand, always within reach, to peruse at night as motivation to go out there and tell my own story.

Robert Frank’s ‘The Americans’: The Art of Documentary Photography by Johnathan Day

1 Comment

Susan Rae

Excellent commentary on The Americans. I love mid-century American photography and will check out Frank’s work.