Dandruff in Cats

Cats are meticulous about their appearance. They take grooming seriously, and most cats maintain a beautiful, spotless hair coat. Occasionally, however, cats will develop (horror of horrors)… dandruff! Of course, dandruff – dry, dead skin cells that flake off from the skin – isn’t a cause of social embarrassment in cats that it is in humans. They couldn’t care less. In most cases, dandruff is simply unsightly, although occasionally it can be an indicator of an underlying medical condition.

Although most veterinary textbooks don’t list dandruff as a symptom of diabetes, in my veterinary practice it is very common for diabetic cats to have dull, dry flaky hair coats. The classic signs of diabetes are excessive thirst and urination, weight loss despite a ravenous appetite, and occasional weakness in the rear legs. Middle-aged (8 to 10 years old) males are more commonly affected. If your cat has dandruff plus the signs listed above, a veterinary visit is warranted to be certain he or she isn’t diabetic.

Obesity is another common cause of dandruff in cats. The most common location for the dandruff is the lower back region, and the reason for that is obvious: these porkers are too chubby to reach around and groom their backs properly!

The most common reason for dandruff is simply dry skin. Here in the northeast, the winters can be pretty dry, and cats will often develop flaky skin, most notably along the lower back, simply from low humidity. Sigh…if only they moisturized after bathing. Treatment of the dandruff depends on the cause. Dandruff is the least of a diabetic cat’s problems. The diabetes should be addressed promptly. Diabetic cats are treated with insulin in conjunction with a high-protein/low-carbohydrate diet. As the diabetes resolves, the dandruff usually goes away as well.

Overweight cats should be put on a diet. Increased physical activity is beneficial for weight loss, but this is easier to accomplish in dogs and people than it is in cats. In cats, the main focus is dietary. Prescription diets for weight loss can be of the high-fiber/low-fat variety, or the high-protein/low-carb variety. Both diets are effective, although the high-protein/low-carb diets may be more suitable, since cats are true carnivores and were not designed to take in too many carbs. Also, in the past, when I used to put an overweight cat (without dandruff) on a low-fat diet, they occasionally developed dandruff. It is more in the cat’s best interest, health-wise, to not be obese compared with a few flakes of dandruff. With the high-protein/low-carb diets, however, inducing dandruff is never a problem.

An otherwise healthy cat with a few flakes of dandruff probably doesn’t require a veterinary visit. However, if the dandruff is prominent and if any other signs of illness are present, you should schedule a veterinary consultation. If your veterinarian agrees that it is just a dry skin problem, you have several options to address the issue. Mild cases can be ignored; a few flakes are no big deal. Grooming the cat with a flea comb (a comb whose teeth are very close together) often helps remove flakes from the coat. In moderate cases, bathing your cat with a “keratolytic” shampoo – one that dissolves flakes – often helps controls the dandruff. Most veterinary offices carry these special shampoos, although one should keep in mind that no cat on earth enjoys being bathed. A fatty acid supplement rich in omega-3 fatty acids often reduces or eliminates dandruff and improves the general appearance of the coat, although it may take several weeks to see the full effect. Omega-3 fatty acids come in a variety of forms – capsules, liquids, and treats. You would think that cats would love these supplements, being that they are derived from fish oil. However, in my experience a significant number of cats (perhaps as much as 40%) despise the taste of them and will refuse food to which these supplements are added.

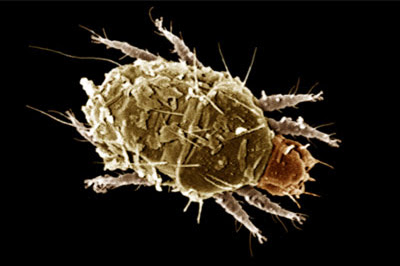

In any article about feline dandruff, Cheyletiella probably bears mentioning. Cheyletiella is a mite that can affect dogs, cats, rabbits and people. They live on the surface of skin, completing their entire life cycle while on the host animal. The most common sign of Cheyletiella is itching and dandruff. The itching is mainly on the back, but it can also be anywhere on the trunk. Dry white scales are often present down the back. When a cat infested with Cheyletiella is examined closely, the dandruff can be seen to be moving, which explains the name “walking dandruff” that is often used to describe Cheyletiella. The movement is actually caused by the mites moving around beneath the dandruff flakes. Cats can develop small scabs all over their body, and symmetrical hair loss can be seen along the sides of the body where the cat might be overgrooming from the itchiness. Diagnosis is made by examining skin scrapings under the microscope, however, because the mites live on the surface of the skin, they may be detected using the “Scotch tape” technique, in which a piece of clear tape is applied to the scaly part of the skin, and is then stained and adhered to a slide for microscopic evaluation. Cheyletiella is easily treated with topical products, such as selametcin (Revolution). Cheyletiella is pretty uncommon, although most veterinarians have seen a few cases in their career (I’ve seen three cases in 29 years).

Kitty dandruff is, in most cases, an unsightly nuisance more than anything. If there’s no underlying medical disorder, then there’s no cause for alarm. Concerned owners can be proactive by avoiding obesity in their cat, brushing the cat regularly, and considering a humidifier during the cold, dry winter months. By doing this, your cat’s hair coat will be head and shoulders above his kitty colleagues. (Sorry, I couldn’t resist that one.)